Chapter 1

RACHEL KRAMER dropped her linen napkin across the morning newspaper’s inflammatory headline: “Cold Spring Harbor Scientist in League with Hitler.” She glanced up, willing herself to smile innocently as her father strode into the formal breakfast room.

“You needn’t bother to hide it.” His eyes, bloodshot and mildly accusing, met hers as he took his chair at the head of the polished mahogany table. “I’ve already received a phone call from the Institute.”

Rachel glanced at their butler’s stoic face as he poured her father’s coffee, then carefully framed her statement. “It isn’t true, of course.”

“In league with the Führer? You believe the ravings of that maniac hack Young?” he scoffed. “Come now, Rachel—” he jerked his napkin from its ring—“you know me better than that.”

“Of course, Father. But I need to understand—”

“Which is why this trip is essential. You’ll see for yourself that those foreign correspondents exaggerate—to sell American papers, no doubt, but at the expense of international relations and good men doing crucial work.”

She might be little more than an inexperienced college graduate, but she wouldn’t be shot down. “He also claims that Hitler accuses the Poles of disturbing the peace of Europe—that he’s blaming them for impending war, creating a ruse to justify an invasion. If that’s true—if he’d truly attack Poland—then you really can’t trust him, Father. And if this reporter is right about that, then people will believe—”

“People will believe what they wish to believe—what is expedient and profitable for them to believe.” He pushed from the table, toast points in hand. “You mustn’t pay attention to the rags. It’s all propaganda. I’m sure Herr Hitler knows what he’s doing. The car will be here any moment. Are you packed?”

“Father, no sane person is going to Germany now. Americans have evacuated.”

“I assure you that I am completely sane.” He stopped and, uncharacteristically, stroked her cheek. “And you are destined for greatness.” He tugged his starched cuffs into place. “Remember, Rachel, it is ‘Herr Hitler.’ The Germans do not take kindly to disrespect.”

“Yes, Father, but you and I—we must have an understanding—”

But he’d already crossed the room, motioning for his coat. “Jeffries, watch for the driver. We mustn’t miss our plane. Where are your bags, Rachel?”

She folded her napkin deliberately, willing her temper into submission—for this trip only . . . until I make you understand that this is my last trip to Frankfurt—to Germany—and that our relationship must drastically change . . . just as soon as we return to New York. “My bags are waiting by the door.”

***

Two days later, Rachel tugged summer-white gloves over her wrists, as if that might erect a strategic barrier between her person and the German city once familiar to her. It had been five years since she’d ridden down the wide, pristine avenues of Frankfurt. The medieval spires and colorful geometric brickwork looked just the same. But every towering, spreading linden tree that had graced the main thoroughfare—each a landmark in its own right—had been ripped from its roots, replaced by steel poles slung with twenty-foot scarlet banners sporting black swastikas on white circles. Ebony spiders soaked in shame.

“There is no need to fret. It won’t be long now. The examination will soon be over. You missed the last one, so you mustn’t object if this one takes a bit longer.” Her father, his hair thinning by the minute, smiled absently, moistened and flattened his lips. “Our train leaves at seven,” he muttered, staring out the window. “We will not be detained.”

She forced her fingers to lie still in her lap. His affected reassurance gave little comfort. Why she’d agreed to the hated biennial physical examination by doctors she detested or to coming to Germany at all, she couldn’t fathom.

Well, yes . . . she could. Rachel sighed audibly and glanced at the too-thin, self-absorbed man beside her. It was because he’d insisted, because they’d argued as never before, because he’d begged, then badgered, and finally ordered. Because, being adopted, she’d known no other father, and because her mother had loved him—at least the way he used to be, the way he was when she was alive. And, significantly, because Rachel’s new employer had agreed to delay her date of hire until September 20.

She leaned back into the comfort of the cool leather seat, forcing herself to breathe. She supposed she could afford him this parting gift of time, this assertion of her belief in him, though she’d come to question—if not doubt—his life’s work.

That work had taken a twisted turn from his quest to eradicate tuberculosis, her mother’s killer. The publicity against his beloved eugenics research was growing, getting ugly, thanks to the outcries of investigative-journalist crusader types at home and abroad. She would be glad to distance herself when the ordeal was done.

Perhaps this peace offering would soften her announcement that she’d been hired by the Campbell Playhouse—as a gofer and underling to start. But if she proved herself indispensable, they might include her in their November move to Los Angeles—one step closer to radio theatre performance. All of which would send her father into a tizzy. He disdained radio theatre more than he’d detested her modern theatre productions in college, blaming the influence of her professors and “theatrical peers” for her independent thinking. She’d tell him the moment they returned to New York. As far as Rachel was concerned, that could not be soon enough.

But there were the medical examination in Frankfurt and the gala in Berlin to endure first—the gala to honor her father and German scientists for their breakthrough work in eugenics. The gala, which would include Gerhardt and her childhood friend Kristine. She brushed the air as if a fly had landed on her cheek. What had Kristine meant in her letter about “Gerhardt, and things impossible to write,” that she was “terrified” for her daughter, Amelie? It was the first letter Rachel had received from her former friend in five years.

She placed one ankle deliberately over the other. Perhaps Kristine’s grown tired of playing the sweet German Hausfrau. It would serve her right for betraying me. Rachel bit her lip. That sounded harsh, even to her.

The black Mercedes skirted the banks of the free-flowing Main and glided at last into the paved drive of the sprawling Institute for Hereditary Biology and Racial Hygiene. The driver—black-booted, square-jawed, the picture of German efficiency in the uniform of the SS—opened her door.

Rachel drew a deep breath. Taking his hand, she stepped onto the walk.

***

Lea Hartman gripped her husband’s hand as she waited her turn in the long, sterile corridor. What a gift that Friederich had been granted a three-day military pass! She couldn’t imagine making the train trip alone, especially with the fearful knot that had grown and tightened in her stomach with every town they’d passed.

She’d been coming to the Institute every two years for as long as she could remember. The money and demand for the examinations had come from the Institute itself, though exactly why, she’d never understood—only that it had something to do with her mother, who’d died giving her birth at the Institute.

As a young child it had afforded the opportunity for a long, exciting train trip with her Oma. Even the doctors’ authoritarian stance and scathing disapproval hadn’t entirely dimmed the joy of the magical journey far from Oberammergau. But as a teen she’d grown shy of the probing doctors, intimidated by the caustic nurses, yet fearful of refusing their demands. At sixteen she’d written, bravely stating that she no longer wished to come, that her health was quite good, and that she no longer saw the purpose. The next week a car from the Institute had screeched to a stop outside her grandmother’s door. Despite Oma’s protests, the driver had produced some sort of contract that Oma had signed when Lea was given to her and raced the teen all the way to Frankfurt—alone. She’d been kept in a white enamel room, in a confined portion of the sterile Institute, for a fortnight. The nurses had woken her hourly; the doctors examined her daily—intimately and thoroughly. Lea dared not refuse again.

She shifted in her seat. Friederich smiled at her, squeezing her hand in reassurance. Lea breathed deeply and leaned back against the wall.

Now she was married—almost eighteen months—and though she dreaded the ritual examination, she dared hope they could tell her why she’d been unable to conceive. There was no apparent reason, and she and Friederich wanted a child—several children—desperately. She closed her eyes and once more begged silently for mercy, for the opening of her womb.

Her husband encircled her with his arm, rubbing the tension from her back. His were the strong, roughened hands of a woodcarver—large and sensitive to the nuances of wood, even more sensitive to her needs, her emotions, her every breath. How she loved him! How she missed him when he was stationed with the First Mountain Division—no matter that the barracks flanked their own Oberammergau. How she feared he might be sent on one of the Führer’s missions to gain more “living space” for the Volk. How she feared he might stop loving her.

The door to the examination room opened.

“Dr. Mengele!” She recognized him from two years before. She would not have chosen this doctor, though she could not say precisely why. The examinations, no matter who performed them, were technically the same. It was only a feeling, and hadn’t they told her countless times not to trust her feelings, her instincts? They were not reliable and would mislead her. Neither they nor she could be trusted.

“May I come with my wife, Herr Doctor?” Friederich stood by her side. Lea felt her husband’s strength seep into her vertebrae.

“For the examination?” Dr. Mengele raised eyebrows in amusement. “Nein.” And then more gruffly, “Wait here.”

“But we would like to talk with you, Herr Doctor,” Friederich persisted, “about a matter of great importance to us.”

“Can a grown woman not speak for herself?” Dr. Mengele’s amusement turned scornful. He didn’t acknowledge Lea, but snorted and walked through the door.

Lea glanced once more into her husband’s worried eyes, felt his courage squeezed into her hand, and followed Dr. Josef Mengele into the examination room.

***

Friederich checked his watch. If the clock in the hallway was to be believed, Lea had been behind the closed door for only forty-seven minutes, but it seemed a lifetime.

He’d not been in favor of her coming to Frankfurt. He’d never understood the hold the Institute maintained over his wife, why she both feared and nearly fawned at the feet of these doctors. But he’d married her—the woman he saw much more in than she saw in herself—for better or for worse, and this, he’d decided, was part of that package. He would not forbid her to come; she feared them too much for that.

And these days, putting your foot down against authority figures carried consequences—consequences Lea could not afford now that Friederich was not regularly at home. The last thing he wanted was men from the Institute on his wife’s doorstep when he was not there to protect her. Better for her to remain invisible. From what little he knew of the Führer’s “negotiations” with Poland, he and his unit could be shipped east at any moment. He’d been lucky to get leave at all.

Friederich pushed his hands through his hair, sat heavily once again on the backless bench, and knotted his fingers between his knees.

He was a simple man. He loved his wife, his Lord and his church, his country, his woodcarving, Oberammergau with all its quirks and passion for its Passion Play. He was a grateful man, and the only thing missing in his life was children that he and Lea would bear and rear. He didn’t think it selfish to ask God for such a thing.

But he wondered if Lea would ask the right questions of the doctor, if she might miss something. She was a smart and insightful woman, but the nearer they’d come to Frankfurt, the more childlike she’d become. And this Dr. Mengele, whoever he was, seemed less than approachable.

Friederich checked his pocket watch, then the clock again. He wanted to take his wife from this place, go home to Oberammergau—home to their cool Alpine valley, to all they knew and loved. He only wished he didn’t have to return to his barracks, wished he could take his wife home and make love to her. It wasn’t that he didn’t want to serve his country or that he loved Germany less than others. At least, he loved the Germany he’d grown up in. But this New Germany—this Germany of the last seven years with its hate-filled Nuremberg Laws that persecuted Jews, its eternal harassment of the church, its constant demand for greater living space and focus on pure Aryan race—was something different, something he could not grasp as a man grasps wood.

Like any German, he’d hoped and cheered when Adolf Hitler had promised to raise his country from the degradation of the Treaty of Versailles. He wanted to be more than a stench in the world’s nostrils and to forge a good life for his family. But not at the expense of what was human or decent. Not if it meant dishonoring God in heaven or making an idol of their Führer.

He closed his eyes to suppress his anxiety about Lea, about politics, to clear his head. This was not the time to argue within himself about things he could not control.

He’d focus on the Nativity carving on his workbench at home. Wood was something he could rely upon. Just before being conscripted, he’d finished the last of a flock of sheep. Now he envisioned the delicate swirls of wood wool and the slight stain he would tell Lea to use in their crevices. Yes, something with a tinge of burnt umber would add depth, create dimension. His wife had the perfect touch. Watching her paint the wooden figures he’d carved was a pleasure to him—a creation they shared.

Friederich was counting the cost of the pigment and stain mixtures she would need for the entire set when the sharp click of a woman’s heels on the polished tile floor caused him to lose focus. Her perfume preceded her. He opened his eyes, only to feel that he’d fallen into another world. There was something about the woman’s face that struck him as frighteningly familiar, but the window dressing was unrecognizable.

Striking. He’d say she was striking. The same medium height. Her eyes were the same clear blue. Her hair the same gold, but not wrapped in braids about her head as they’d been an hour ago. Her locks hung loose, in rolling coils, so fluid they nearly shimmered. Her nails—fiery red—matched her lips. She wore seamed stockings the color of her skin and slim, high-heeled shoes that, when she paused and half turned toward the door, emphasized slender ankles and showed toned calves to good advantage.

All of that he noticed before he took in the belted sapphire suit, trim and fitted in all the right places. He closed his eyes and opened them again. But she was still there, and coming closer.

The thin, middle-aged man beside her stepped in front, blocking his view. “Entschuldigung, is this where we wait for Dr. Verschuer?”

But Friederich couldn’t speak, couldn’t quite think. And he didn’t know a Dr. Verschuer—did he?

At that moment a pale and agitated woman in nurse’s uniform pushed through the door at the far end of the corridor, hurrying toward them. “Dr. Kramer—please, you have entered the wrong corridor. Dr. Verschuer is this way.” Casting a furtive glance toward Friederich, she hurried the man with the thinning gray hair and the beautiful young woman back the way they’d come.

“Lea,” Friederich whispered. “Lea,” he called louder.

The woman in the belted suit turned. He stepped expectantly toward her, but her eyes held no recognition of him. The nurse grabbed the woman’s arm, pulling her down the hallway and through the door.

Friederich stood half a moment, uncertain what he should do, if he should follow her. And then the examination room door beside him opened, and his wife, her face stricken and braids askew, walked into his arms.

Chapter 2

GERHARDT SCHLICK pulled a cigarette from its silver case and drew the fragrant tobacco beneath his nostrils. He was appreciative of the little things that life in the SS afforded—good food, good wine, beautiful women, and the occasional gift of American tobacco.

He smiled as he lit his cigarette and inhaled—long and slowly. After tonight he expected to replenish his stock of at least two of those items. The rest would come in due course to a man of his station. He checked his reflection. More than satisfied, he squared his shoulders and tugged the coat of his dress uniform into place. Then he checked the clock, and his mouth turned grim.

“Kristine!” he barked. It would not do to be late—not tonight. Every SS officer of note in Berlin would be there, including Himmler, and every Nazi Party man of letters. Only the Führer would be absent, and that, Gerhardt was certain, was by Goebbels’s design—some scheme for greater propaganda, no doubt.

It was an evening to honor those entrusted with designs to strengthen Germany’s bloodline through eugenics—to create a pure race, free of the weaknesses introduced by inferior breeding with non-Nordic races. It was nothing short of a drive to rapidly increase Germany’s Nordic population. A perfect plan to restore Germany to its rightful position in the world—over the world.

Within that grand design Gerhardt saw himself rising through the ranks of the SS. Marrying the highly acceptable adopted daughter of eminent American scientist Dr. Rudolph Kramer would be one more rung in that ladder. A perfect blending of Germanic genes—Nordic features, physical strength and beauty, intellect . . . a perfect family for the Reich.

He smiled again. He wouldn’t mind doing his duty for the Fatherland, not with Rachel Kramer.

He could count on Dr. Verschuer and Dr. Mengele. And he suspected, since this afternoon’s telephone call from the Institute, that with minimal persuasion he could also count on the cooperation of Dr. Kramer where his daughter was concerned.

One thing stood in his way. Perhaps two.

At that moment Kristine Schlick walked into the room. She twirled self-consciously. The ice-blue satin evening gown brought lights to her eyes as it floated, rippling round her shapely form.

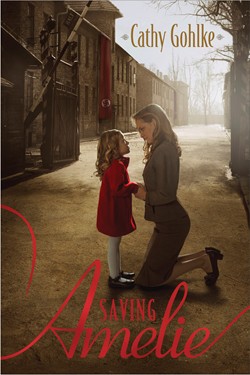

Their four-year-old daughter, Amelie, clapped delightedly as her mother twirled. Kristine lifted the child in her arms and planted a kiss on her cheek. Amelie patted her mother’s cheeks and gurgled an inharmonious stream of syllables.

Taken off guard, Gerhardt felt his eyes widen. There was no doubt that his wife was beautiful. Breathtaking—he would give her that. And there were other acceptable features. But she bore genetically deficient children, and in the New Germany that was unforgivable.

“Well?” she asked tentatively. “Do you like it?”

The question of a woman who knows the answer but is afraid to believe. The question of a woman who begs to be told she is beautiful.

But Gerhardt disdained begging as much as he disdained Kristine and his unacceptably deaf daughter. Turning off emotion—any form of weakness—was not difficult once he’d set his mind to it. And he had. He slapped his evening gloves against his thigh, ignoring the sudden terror in the eyes of his child as her mother set her on the floor, shielding her from his approach. “The car is waiting. You’ve made us late.”

***

Rachel turned one way before the full-length mirror in her hotel room, tilted her head, then turned the other. She loved green. But wearing it for the gala would’ve been fodder for yet another argument with her father. He’d insisted she wear royal blue, in a style that would frame her face and set her eyes and hair to best advantage. Because the gala would honor him and his work, celebrating the eugenics research shared between the two countries and the world, he’d asserted that it was essential, especially in these uncertain times, to appear their best and most gracious in every way. Rolling her eyes, she’d acquiesced.

She had to admit that the deep color, draped neckline, and fluid silk did more for her than anything she owned. And because it was the color he’d chosen, her father had not balked at the outrageous price. She supposed it would come in handy for events in New York City—maybe the opera house or a first night at Radio City Music Hall.

Rachel lifted her chin and straightened her spine. She didn’t mind turning heads, and she wouldn’t mind showing up Kristine and Gerhardt Schlick. She mightn’t have cared if Kristine had kept in touch. That’s what hurt most—her sudden abandonment.

She’d always known that Kristine wanted a life, a husband and family of her own—those were things girls told one another. And why not? Kristine was a warm, intelligent, and beautiful woman in her own right. Rachel admitted—if only to herself—that she’d relegated her friend to the shadows too often, too long.

Kristine had been so quick to comfort Gerhardt’s wounded pride five years ago when he’d stood in the Kramers’ New York parlor, furious and unbelieving, his marriage proposal rejected by nineteen-year-old Rachel. He’d married Kristine to spite her; of that she was certain. But Kristine had married him because she’d been swept off her feet, eager for her moment in the sun, her time to shine on distant German shores without Rachel to dim her reflection.

If she regrets her choice now . . . well, what is that to me?

“Rachel?” Her father knocked at her door. “It’s time.”

“Coming,” she called, pulling her light wrap over her shoulders and applying a last deliberate swipe of lipstick. She blotted, picked up the blue-and-silver silk purse dyed to match her shoes, and marched toward the arena.

***

Jason Young checked his hat outside the lavish ballroom door, tightened the knot in his tie, and squared his shoulders. He couldn’t believe his luck. For two years he’d tracked the elusive Dr. Rudolph Kramer through Cold Spring Harbor’s Eugenics Research Association. Not once had the “mad scientist,” as Jason had dubbed him, been available for an interview on either side of the Atlantic—and Kramer visited Germany frequently. Not once had he returned the phone calls his secretary promised he would. But that hadn’t kept Jason from dishing up the dirt on the man’s research and splattering it across news copy—research Jason saw as inhumane and, with Germany’s unchecked collusion and Hitler’s sterilization campaign, inescapably criminal.

But those obstacles were past. Because tonight he had a press pass to the gala—a legitimate opportunity to watch and record, word for word, everything the man and his cohorts said. If all went well, he’d get directly in Kramer’s face before the clock struck midnight. Jason wasn’t about to miss this flying saucer to stardom. “Watch out, Pulitzer, here I come!” he whispered.

“Hold on, hotshot.” Daren Peterson laid a hand on his colleague’s shoulder, gently pushing him toward a linen-covered table with a direct view of Rudolph Kramer and his stunning daughter. “All things in time. Let the man get comfortable. Let him get through his glad-handing. Then I’ll shoot the artwork and you can eat him alive.”

Jason rubbed his hands together and licked his lips.

***

Rachel had had more than enough. Nearly three hours of sanctimonious speeches on the growth of Aryan purity and toasts brimming with laudations for the scientific community’s systematic plans to rid the world of diseased and inferior stock had passed before the music and dancing, the serious tippling of champagne, and the ultimate loosening of tongues began.

She’d felt undressed by nearly every roving masculine eye and sized up and scathed by every feminine one. Gerhardt Schlick’s undisguised stare reminded her of Margaret Mitchell’s scene in Gone with the Wind—when Rhett Butler’s gaze seared Scarlett O’Hara ascending the stairs of Twelve Oaks. Only she doubted that Gerhardt’s intentions were as gentlemanly as the ungentlemanly Rhett’s.

She actually felt sorry for Kristine. Gerhardt had clearly distanced himself from his wife, paying her mind only to reprimand her with openly superior and snide remarks. Kristine, though tipsy, just as clearly felt his rebukes.

“You must dance,” her father whispered, distracting her from watching the couple on the inside of the horseshoe-shaped seating arrangement several feet away.

Rachel bristled. “I don’t want to dance.”

“Allow me.” He stood and, ignoring her response, led her to the dance floor.

At least it was better than dancing with the SS officers or the fawning Dr. Mengele. Rachel was always surprised and pleased when dancing with her father. The moment he stepped onto a dance floor his carriage, his entire demeanor, changed from intent, slump-shouldered scientist to man about town. He bowed, lifted her hand, and they began a Viennese waltz. Perfect frame, perfect timing with the orchestra, and just the right pressure on her back, against her hand. Ballroom dancing was something he and her mother had shared, and though Rachel could not waltz as wonderfully as she remembered her mother waltzing, in his arms she knew she could be made more beautiful still.

They’d taken one sweeping turn round the ballroom floor when her father stopped in response to a tap on his shoulder. He smiled, bowed slightly, and stood aside.

Sturmbannführer Gerhardt Schlick was waiting, smiling in a way that made Rachel shudder, though she refused to show it. She allowed herself to be led round the floor. On the second turn he pulled her closer. “It’s been a long time. It’s good to see you again, Rachel.”

She swallowed, smiling confidently, but her throat was dry. “Has it? And how is Kristine, and your daughter?”

A coldness passed through his eyes. “You must judge that for yourself.”

She raised her brows.

He sighed. “Oh, come now. There must have been signs before. You should have told me, warned me. I thought we were friends, at least.”

“I’ve no idea what you’re talking about.”

“Your friend is not—” he hesitated—“genetically sound. She is not emotionally . . . I would use the English word stable.”

“Kristine is more stable than any girl I know.”

“And so I thought when I agreed to marry her. But as I said, you must judge for yourself.”

“What have you done to her?”

He looked the aggrieved, terribly injured party. “You wound me, Fräulein, and do me injustice.”

“I doubt that very much.”

“Ever the champion of the underdog.” He smiled. “And as beautiful as the moment I first saw you.” He pulled her closer still.

“And you are married, Herr Schlick.” She stepped away from him.

He snorted softly. “Truly, my mistake.” Gerhardt bowed, but held her hand and kissed it. “I should have waited for you, no matter how long.”

She turned, but he did not let go of her hand. “You’ll be in Berlin for several weeks, I understand, Fräulein Kramer.”

She didn’t respond.

“I look forward to seeing more of you, and often.”

“That will not be possible.” Rachel pulled away, more disgusted than frightened. She sensed that he followed her toward her seat. Her father was not there, but standing oblivious, deep in conversation within the doctors’ circle several feet away. Kristine was gone.

All the you-should-have-known-better cuts she’d loaded in her arsenal, ready to aim at Kristine, evaporated. No matter the headlong foolishness of her rebound marriage, Kristine didn’t deserve Gerhardt Schlick.

Rachel retrieved her bag from the table and headed for the ladies’ room, trusting that Gerhardt would not follow.

Chapter 3

DESPITE CLOSE PROXIMITY and creative lurking, Jason Young had not maneuvered one minute alone with Dr. Kramer. “Himmler’s got him smothered and Verschuer’s got him dwarfed.”

“Kramer’s a pale fish out of water,” Peterson agreed. “Doesn’t look like much beside those SS and the charismatic Mengele.”

“So, who does? I’m thinking we’d all ought to wear jackboots and carry riding crops.”

“Well then, what’s next?” Peterson grumbled, licking the base of a new flashbulb.

“They don’t want him alone with the press. We’ve got to get him off to the side.” Jason edged toward the tight clique of officers and doctors.

“Muscle through that crowd and you’ll find yourself on a swift vacation to hard labor,” Peterson whispered. “Perfect opportunity to buddy up with those concentration-camped German priests and pastors you love to champion.” He twisted the bulb into his camera, smiling into the face of a particularly nasty-looking SS officer with a monocle.

Jason pushed a hank of sandy hair from his eyes. “We’re not supposed to know about that.”

“Right,” Peterson snorted. “Neither is half of Germany.”

“And I don’t do prison interviews—nasty smells.”

“Wasn’t trying to be funny.”

Jason skirted the small group, trying to ingratiate himself into the conversation, person by person. But it was no use. It was as though they’d formed a seal around the American scientist.

Except that Jason knew the great doctor was fluent in German, he might have suspected Kramer did not understand the speeches—those from the platform or those given by the men standing next to him. Pretty radical rhetoric, even for the mad scientist. He didn’t appear the pompous, driven man Jason had shadowed in New York City. So what’s changed?

Peterson nudged him. “You’re not the only vulture circling.” He nodded toward Kramer’s daughter, who seemed to be trying to capture her father’s attention. “Why not try the circuitous route?”

Rachel Kramer wasn’t his first choice. Jason doubted she was privy to her father’s research or the alliance between the Eugenics Research Association and the Third Reich. He’d checked her out for just that purpose back in New York but had been convinced she had her head buried in modern theatre. He reconsidered now, giving her the once-over, head to toe—all business. Then he did it again—pure pleasure. She just might be a link to the great doctor off court.

He swallowed. That was an excuse, and he knew it. It wouldn’t do to get distracted. Beautiful women had a way of doing that. Still, it was worth a try. He stepped closer and opened his mouth to speak.

“Rachel.” A black dress SS uniform muscled between them, pulling her from the group. “I must speak with you.”

But she turned on the German. “I don’t wish to speak with you. Take your hands off me.”

“Please, my dear, let’s not make a scene. Consider your father.” The SS uniform leaned closer, wrapped his arm around her, but she struggled against him.

“We’re on.” Jason elbowed Peterson and pocketed his notepad and pencil, picked up a glass of champagne from the nearest place setting, and slammed into the SS officer. “Entschuldigung, Herr Sturmbannführer. My fault entirely.”

“You imbecile!” the officer exploded, releasing Rachel.

“You’re absolutely right; I’m a clumsy oaf. Here—” Jason grabbed a linen napkin, dramatically sopping the man’s arm—“let’s clean you up.”

“Get away from me, you Dummkopf!”

“Now, now.” Peterson stepped between the two, steering the officer away. “There’s no need to get riled. International relations and such. Simple mistake. How about I get your photograph for the newspaper? What was your name again?”

Jason just as smoothly cupped Rachel’s elbow. “Would you care to dance, Miss Kramer? Give this homesick American a Berlin memory?”

Clearly relieved, Rachel stepped onto the dance floor. “Thank you. That was—”

“Uncomfortable,” Jason finished. He took her hand, twirled her twice, then pulled her closer than necessary into a fox-trot. “Damsel in distress from the nasty Nazis and all that.”

Rachel laughed, pulling back slightly. “Precisely. And who is this chivalrous Yank I must thank?”

“Sir Jason, at your service.” He mocked a bow.

She mocked a curtsy, smiling warmly. Jason felt his blood race.

“Well, Sir Jason, what brings you to Berlin? It’s not exactly tourist season in the nation’s capital, is it?”

“Hardly.” Jason took a half box turn to keep Peterson and the uniform in his peripheral vision. “First big gala assignment in the new regime.”

“You’re a foreign correspondent?”

He felt her tense. Jason laughed. “From your mouth to my editor’s ears! Confidentially—” he twirled her again—“I’m guessing he’s laying ten to one that I’ll fall flat on my face before the New Year, get kicked out of the country by the Gestapo, and be back on NY’s city beat before you can catch a cat’s meow.”

“You’re that bad?”

He grimaced. “Do you always say exactly what you mean?”

Now she laughed. “I hope so. I don’t have a journalist’s gift for flattery.”

“You give me too much credit.” He dipped her once.

“And you’re a flamboyant dancer!”

“Not so staid and serious as your German uniform?” He grinned, though he caught the uniform’s glare from across the room.

She shuddered—enough that he felt it through her evening gown.

“So, who is the creep?”

“The husband of an old friend—who’s acting like neither.”

“Check. Do you want me to walk you out?”

“No, no, of course not—thank you. I’m here with my father.” She nodded toward the clique against the far wall.

“Not one of the military types, I take it.”

“No. The American scientist—Dr. Kramer.” She lifted her chin slightly but diverted her eyes. Jason caught her mixed glimmer of pride and uncertainty.

“Ah—part of the cooperative eugenics program Himmler was going on about.”

“I’m fairly certain Herr Himmler overemphasized America’s contribution.”

“No need to be modest. It’s all the rage here in Germany—master Nordic race breeding. Sterilization of questionable bloodlines. Elimination of undesirable elements.” He twirled her again. “So, what do you make of it?”

She looked taken aback, and Jason knew he was losing her. “What does your father think? Will the US be accelerating their program—keep pace with the Führer?”

Her smile gone, she pulled away. “I don’t discuss politics, Mr.—Mr. Jason.”

He raised his hands in surrender. “My apologies, Miss Kramer. No offense intended. It’s just that this is a gala to celebrate the research shared between countries. I figured you’d be all for it, or at least your father would.” He stepped closer, staged his best repentant-little-boy look, and held out his hand. “I’ll behave. Promise.”

She placed her hand in his.

Jason couldn’t believe his luck. “Here’s something neutral. What will you do while in Germany? Need a tour guide?”

“I’ve been coming to Germany ever since I was a child. What could you show me?”

“Anything you want. Say the word.” He grinned. “I’ll become the best tour guide Germany has to offer, if I have to bribe every cabbie in Berlin!”

At last she smiled, and he twirled her, glad to be in her favor once again.

“As a matter of fact, Sir Jason, I probably know Berlin better than you. Perhaps I should give you the tour.”

“Now you’re talking!”

“But only if you stop twirling me—I’ll be too dizzy to walk!”

They both laughed as the music faded.

“Thirsty?”

“I thought you’d never ask.”

Before they lifted champagne flutes from the waiter’s tray, Peterson cut in. “Young, I’m out of here. I need to get these photos developed. See you tomorrow.” He nodded appreciatively toward Rachel. “Miss Kramer.”

But when Jason turned back to Rachel, her jaw had gone rigid and her eyes cold. “Young? Your name is Young? Jason Young?”

Jason swallowed, fairly certain what was coming.

“The bounty hunter masquerading as a crusader out to ruin my father?”

“Hey, that’s not my intention.”

“You knew my name. You knew who I was. That’s why you danced with me—you wanted a story.”

“I don’t rescue women in distress to get a story. I didn’t set up the uniform. You looked like you could use some help.” But he couldn’t hold her piercing gaze.

“Your incessant hounding is driving my father into an early grave.”

“My hounding?” He couldn’t let that pass. “Do you know what they’re doing as a result of his research and the research of his counterparts here in Germany? Did you hear what they said tonight?”

Rachel turned to walk away, but Jason kept pace. “If he’s innocent, if there’s a good side to this, then help me get the story. Convince him to talk to me. I’ll be fair—honest.”

“Honest?” She nearly snorted, reducing him to dung with her glare. “You’ve shown just how honest you are, Mr. Young. I don’t think either Germany or America can stand much more of your brand of honesty.”

Jason stopped short, the wind knocked from his sails. “Hey, I don’t make the news,” he called after her. “It’s people like your father who do that! I just write it.”

***

The piercing headache between Rachel’s eyes would not relent. Even the headlights of oncoming cars made her wince. But her father was in high spirits.

“Quite the affair, if I do say so.” He spoke as if expecting an answer, but Rachel knew better. She closed her eyes and leaned back against the seat of the Mercedes.

“I daresay Herr Himmler came across rather stronger than I would have, but Germany’s on the right track. They’ve moved ahead of us in America. We’ll benefit greatly from their studies.”

She turned away, uncertain which was the culprit that made her feel sick—her headache or her father’s skewed reality.

“We’ll be leaving for the conference on Tuesday. I’m driving to Hamburg with Major Schlick and Dr. Verschuer, then taking the ship to Scotland. There will be meetings after the conference. Two weeks is a long time on your own.”

“I prefer it. I’d like to do some shopping while we’re in the city, and I’m eager to see what the local theatres are producing.” She tried to push back the throbbing. “I didn’t know Gerhardt was part of the eugenics conference.”

“He’s taken an interest. He’s quite the favorite with Dr. Verschuer. Someone worth knowing . . . a rising star in the SS.”

She felt her father’s eyes upon her, even in the darkness. The thought of Gerhardt Schlick numbered among Germany’s finest made her queasy.

“The trip would give you opportunity to get to know him better.”

“I have no desire to know him better. He was beastly tonight—to his wife and to me.”

“I don’t imagine their marriage will last.”

“Why do you say that?”

Now he turned his head away, toward the opposite window. “You saw how things are between them.” He hesitated, but only a moment. “Did you speak with Kristine?”

“No.” Rachel felt her exasperation rising. “I’d intended to, but we were not sitting near enough during the speeches, and by the end of dinner she was completely cowed by Gerhardt.”

“She was drunk.”

“I can see why. He’s horrid to her.”

“You don’t know what he contends with. You mustn’t judge harshly.”

“Harshly?”

“It was a poor match from the start. You could have handled him so much better. You were . . . hasty.”

Rachel could not believe her ears. Surely her father must have had too much to drink. “What about their daughter? Amelie must be—what—four, by now?”

But her father dismissed her and the notion of Amelie with a flick of the wrist. Rachel was just as glad to drop the conversation. Perhaps by morning he’d regain his senses.

***

Rachel woke to find a note pushed beneath her door. Her father had gone out to an early breakfast meeting with colleagues. He’d apologized that she must eat alone and promised to see her that evening for dinner. They were invited to join the American ambassador and his wife. Rachel knew it was an order.

She opened the balcony door of her hotel room, glad for the morning sun, glad she would not need to spend the day with her father and his cronies. Rather than call for room service, she decided to go exploring—find an outdoor café specializing in strong ersatz German coffee and good rolls.

She was nearly out the door when she remembered her room key. Rummaging through her evening bag, she pulled out her comb and lipstick, her compact and passport—but no room key. She turned the bag upside down. Still no key. She massaged the purse all round, could feel the key in the bottom, but couldn’t see it. Taking her bag to the window, she opened it. When it was held up to the light, she saw that a hole had been torn in the lining—a hole she knew was not there before. Rachel wriggled her finger through, felt the errant key . . . and something else.

She tried to grab hold of the paper, but both slipped away. Retrieving her nail scissors, she snipped the hole a little larger. Out came the key and a slim, rolled paper. Rachel recognized the hastily scrawled handwriting as Kristine’s.