CHAPTER 1

1898–1908

The Soft Hills of Down: An Irish Childhood

“I was born in the winter of 1898 at Belfast, the son of a solicitor and of a clergyman’s daughter.” On 29 November 1898, Clive Staples Lewis was plunged into a world that was simmering with political and social resentment and clamouring for change. The partition of Ireland into Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland was still two decades away. Yet the tensions that would lead to this artificial political division of the island were obvious to all. Lewis was born into the heart of the Protestant establishment of Ireland (the “Ascendancy”) at a time when every one of its aspects—political, social, religious, and cultural—was under threat.

Ireland was colonised by English and Scottish settlers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, leading to deep political and social resentment on the part of the dispossessed native Irish towards the incomers. The Protestant colonists were linguistically and religiously distinct from the native Catholic Irish. Under Oliver Cromwell, “Protestant plantations” developed during the seventeenth century—English Protestant islands in an Irish Catholic sea. The native Irish ruling classes were quickly displaced by a new Protestant establishment. The 1800 Act of Union saw Ireland become part of the United Kingdom, ruled directly from London. Despite being a numerical minority, located primarily in the northern counties of Down and Antrim, including the industrial city of Belfast, Protestants dominated the cultural, economic, and political life of Ireland.

Yet all this was about to change. In the 1880s, Charles Stewart Parnell (1846–1891) and others began to agitate for “Home Rule” for Ireland. In the 1890s, Irish nationalism began to gain momentum, creating a sense of Irish cultural identity that gave new energy to the Home Rule movement. This was strongly shaped by Catholicism, and was vigorously opposed to all forms of English influence in Ireland, including games such as rugby and cricket. More significantly, it came to consider the English language as an agent of cultural oppression. In 1893 the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge) was founded to promote the study and use of the Irish language. Once more, this was seen as an assertion of Irish identity over and against what were increasingly regarded as alien English cultural norms.

As demands for Home Rule for Ireland became increasingly forceful and credible, many Protestants felt threatened, fearing the erosion of privilege and the possibility of civil strife. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Protestant community in Belfast in the early 1900s was strongly insular, avoiding social and professional contact with their Catholic neighbours wherever possible. (C. S. Lewis’s older brother, Warren [“Warnie”], later recalled that he never spoke to a Catholic from his own social background until he entered the Royal Military College at Sandhurst in 1914.) Catholicism was “the Other”—something that was strange, incomprehensible, and above all threatening. Lewis absorbed such hostility towards—and isolation from—Catholicism with his mother’s milk. When the young Lewis was being toilet trained, his Protestant nanny used to call his stools “wee popes.” Many regarded, and still regard, Lewis as lying outside the pale of true Irish cultural identity on account of his Ulster Protestant roots.

The Lewis Family

The 1901 Census of Ireland recorded the names of everyone who “slept or abode” at the Lewis household in East Belfast on the night of Sunday, 31 March 1901. The record included a mass of personal details—relationship to one another, religion, level of education, age, sex, rank or occupation, and place of birth. Although most biographies refer to the Lewis household as then residing at “47 Dundela Avenue,” the Census records them as living at “House 21 in Dundella [sic] Avenue (Victoria, Down).” The entry for the Lewis household provides an accurate snapshot of the family at the opening of the twentieth century:

- Albert James Lewis, Head of Family, Church of Ireland, Read & Write, 37, M, Solicitor, Married, City of Cork

- Florence Augusta Lewis, Wife, Church of Ireland, Read & Write, 38, F, Married, County Cork

- Warren Hamilton Lewis, Son, Church of Ireland, Read, 5, M, Scholar, City of Belfast

- Clive Staples Lewis, Son, Church of Ireland, Cannot Read, 2, M, City of Belfast

- Martha Barber, Servant, Presbyterian, Read & Write, 28, F, Nurse—Domestic Servant, Not Married, County Monaghan

- Sarah Ann Conlon, Servant, Roman Catholic, Read & Write, 22, F, Cook—Domestic Servant, Not Married, County Down

As the Census entry indicates, Lewis’s father, Albert James Lewis (1863–1929), was born in the city and county of Cork, in the south of Ireland. Lewis’s paternal grandfather, Richard Lewis, was a Welsh boilermaker who had immigrated to Cork with his Liverpudlian wife in the early 1850s. Soon after Albert’s birth, the Lewis family moved to the northern industrial city of Belfast, so that Richard could go into partnership with John H. MacIlwaine to form the successful firm MacIlwaine, Lewis & Co., Engineers and Iron Ship Builders. Perhaps the most interesting ship to be built by this small company was the original Titanic—a small steel freight steamer built in 1888, weighing a mere 1,608 tons.

Yet the Belfast shipbuilding industry was undergoing change in the 1880s, with the larger yards of Harland and Wolff and Workman Clark achieving commercial dominance. It became increasingly difficult for the “wee yards” to survive economically. In 1894, Workman Clark took over MacIlwaine, Lewis & Co. The rather more famous version of the Titanic—also built in Belfast—was launched in 1911 from the shipyard of Harland and Wolff, weighing 26,000 tons. Yet while Harland and Wolff’s liner famously sank on its maiden voyage in 1912, MacIlwaine and Lewis’s much smaller ship continued to ply its trade in South American waters under other names until 1928.

1.1 Royal Avenue, one of the commercial hubs of the city of Belfast, in 1897. Albert Lewis established his solicitor’s practice at 83 Royal Avenue in 1884, and continued working from these offices until his final illness in 1929.

Albert showed little interest in the shipbuilding business, and made it clear to his parents that he wanted to pursue a legal career. Richard Lewis, knowing of the excellent reputation of Lurgan College under its headmaster, William Thompson Kirkpatrick (1848–1921), decided to enrol Albert there as a boarding pupil. Albert formed a lasting impression of Kirkpatrick’s teaching skills during his year there. After Albert graduated in 1880, he moved to Dublin, the capital city of Ireland, where he worked for five years for the firm of Maclean, Boyle, and Maclean. Having gained the necessary experience and professional accreditation as a solicitor, he moved back to Belfast in 1884 to establish his own practice with offices on Belfast’s prestigious Royal Avenue.

The Supreme Court of Judicature (Ireland) Act of 1877 followed the English practice of making a clear distinction between the legal role of “solicitors” and “barristers,” so that aspiring Irish lawyers were required to decide which professional position they wished to pursue. Albert Lewis chose to become a solicitor, acting directly on behalf of clients, including representing them in the lower courts. A barrister specialised in courtroom advocacy, and would be hired by a solicitor to represent a client in the higher courts.

Lewis’s mother, Florence (“Flora”) Augusta Lewis (1862–1908), was born in Queenstown (now Cobh), County Cork. Lewis’s maternal grandfather, Thomas Hamilton (1826–1905), was a Church of Ireland clergyman—a classic representative of the Protestant Ascendancy that came under threat as Irish nationalism became an increasingly significant and cultural force in the early twentieth century. The Church of Ireland had been the established church throughout Ireland, despite being a minority faith in at least twenty-two of the twenty-six Irish counties. When Flora was eight, her father accepted the post of chaplain to Holy Trinity Church in Rome, where the family lived from 1870 to 1874.

In 1874, Thomas Hamilton returned to Ireland to take up the position of curate-in-charge of Dundela Church in the Ballyhackamore area of East Belfast. The same temporary building served as a church on Sundays and a school during weekdays. It soon became clear that a more permanent arrangement was required. Work soon began on a new, purpose-built church, designed by the famous English ecclesiastical architect William Butterfield. Hamilton was installed as rector of the newly built parish church of St. Mark’s, Dundela, in May 1879.

Irish historians now regularly point to Flora Hamilton as illustrating the increasingly significant role of women in Irish academic and cultural life in the final quarter of the nineteenth century. She was enrolled as a day pupil at the Methodist College, Belfast—an all-boys school, founded in 1865, at which “Ladies’ Classes” had been established in response to popular demand in 1869. She attended for one term in 1881, and went on to study at the Royal University of Ireland in Belfast (now Queen’s University, Belfast), gaining First Class Honours in Logic and Second Class Honours in Mathematics in 1886. (As will become clear, Lewis failed to inherit anything of his mother’s gift for mathematics.)

When Albert Lewis began to attend St. Mark’s, Dundela, his eye was caught by the rector’s daughter. Slowly but surely, Flora appears to have been drawn to Albert, partly on account of his obvious literary interests. Albert had joined the Belmont Literary Society in 1881, and was soon considered one of its best speakers. His reputation as a man of literary inclinations would remain with him for the rest of his life. In 1921, at the height of Albert Lewis’s career as a solicitor, Ireland’s Saturday Night newspaper featured him in a cartoon. Dressed in the garb of a court solicitor of the period, he is depicted as holding a mortarboard under one arm and a volume of English literature under the other. Years later, Albert Lewis’s obituary in the Belfast Telegraph described him as a “well read and erudite man,” noted for literary allusions in his presentations in court, and who “found his chief recreation away from the courts of law in reading.”

After a suitably decorous and extended courtship, Albert and Flora were married on 29 August 1894 at St. Mark’s Church, Dundela. Their first child, Warren Hamilton Lewis, was born on 16 June 1895 at their home, “Dundela Villas,” in East Belfast. Clive was their second and final child. The Census return of 1901 indicates that the Lewis household then had two servants. Unusual for a Protestant family, the Lewises employed a Catholic housemaid, Sarah Ann Conlon. Lewis’s long-standing aversion to religious sectarianism—evident in his notion of “mere Christianity”—may have received a stimulus from memories of his childhood.

From the outset, Lewis developed a close relationship with his elder brother, Warren, which was reflected in their nicknames for each other. C. S. Lewis was “Smallpigiebotham” (SPB) and Warnie “Archpigiebotham” (APB), affectionate names inspired by their childhood nurse’s frequent (and apparently real) threats to smack their “piggybottoms” unless they behaved properly. The brothers referred to their father as the “Pudaitabird” or “P’dayta” (because of his Belfast pronunciation of potato). These childhood nicknames would become important once more as the brothers reconnected and reestablished their intimacy in the late 1920s.

Lewis himself was known as “Jack” to his family and friends. Warnie dates his brother’s rejection of the name Clive to a summer holiday in 1903 or 1904, when Lewis suddenly declared that he now wished to be known as “Jacksie.” This was gradually abbreviated to “Jacks,” and finally to “Jack.” The reason for this choice of name remains obscure. Although some sources suggest that the name “Jacksie” was taken from a family dog that died in an accident, there is no documentary evidence in support of this.

The Ambivalent Irishman: The Enigma of Irish Cultural Identity

Lewis was Irish—something that some Irish seem to have forgotten, if they knew it at all. While I myself was growing up in Northern Ireland during the 1960s, my recollection is that when Lewis was referred to at all, it was as an “English” writer. Yet Lewis never lost sight of his Irish roots. The sights, sounds, and fragrances—not, on the whole, the people—of his native Ireland evoked nostalgia for the later Lewis, just as they subtly but powerfully moulded his descriptive prose. In a letter of 1915, Lewis fondly recalls his memories of Belfast: “the distant murmuring of the ‘yards,’” the broad sweep of Belfast Lough, the Cave Hill Mountain, and the little glens, meadows, and hills around the city.

Yet there is more to Lewis’s Ireland than its “soft hills.” Its culture was marked by a passion for storytelling, evident both in its mythology and its historical narratives, and in its love of language. Yet Lewis never made his Irish roots into a fetish. They were simply part of who he was, not his defining feature. As late as the 1950s, Lewis regularly spoke of Ireland as his “home,” calling it “my country,” even choosing to spend his belated honeymoon with Joy Davidman there in April 1958. Lewis had inhaled the soft, moist air of his homeland, and never forgot its natural beauty.

Few who know County Down can fail to recognise the veiled Irish originals which may have inspired some of Lewis’s beautifully crafted literary landscapes. Lewis’s depiction of heaven in The Great Divorce as an “emerald green” land echoes his native country, just as the dolmens at Legananny in County Down, Belfast’s Cave Hill Mountain, and the Giant’s Causeway all seem to have their Narnian equivalents—perhaps softer and brighter than their originals, but still bearing something of their imprint.

Lewis frequently referred to Ireland as a source of literary inspiration, noting how its landscapes were a powerful stimulus to the imagination. Lewis disliked Irish politics and was prone to imagine a pastoral Ireland composed solely of soft hills, mists, loughs, and woods. Ulster, he once confided to his diary, “is very beautiful and if only I could deport the Ulstermen and fill their land with a populace of my own choosing, I should ask for no better place to live in.” (In certain ways, Narnia can be seen as an imaginary and idealised Ulster, populated with creatures of Lewis’s imagination, rather than Ulstermen.)

The term Ulster needs further explanation. Just as the English county of Yorkshire was divided into three parts (the “Ridings,” from the Old Norse word for “a third part,” thrithjungr), the island of Ireland was originally divided into five regions (Gaelic cúigí, from cóiced, “a fifth part”). After the Norman conquest of 1066, these were reduced to four: Connaught, Leinster, Munster, and Ulster. The term province now came to be preferred to the Gaelic cúige. The Protestant minority in Ireland was concentrated in the northern province of Ulster, which consisted of nine counties. When Ireland was partitioned, six of these nine counties formed the new political entity of Northern Ireland. The term Ulster is today often used as synonymous with Northern Ireland, with the term Ulsterman tending to be used—though not consistently—to designate “a Protestant inhabitant of Northern Ireland.” This is done despite the fact that the original cúige of Ulster also included the three counties of Cavan, Donegal, and Monaghan, now part of the Republic of Ireland.

1.2 C. S. Lewis’s Ireland.

Lewis returned to Ireland for his annual vacation almost every year of his life, except when prevented by war or illness. He invariably visited the counties of Antrim, Derry, Down (his favourite), and Donegal—all within the province of Ulster, in its classic sense. At one point, Lewis even considered permanently renting a cottage in Cloghy, County Down, as the base for his annual walking holidays, which often included strenuous hikes in the Mountains of Mourne. (In the end, he decided that his finances would not stretch to this luxury.) Although Lewis worked in England, his heart was firmly fixed in the northern counties of Ireland, especially County Down. As he once remarked to his Irish student David Bleakley, “Heaven is Oxford lifted and placed in the middle of County Down.”

Where some Irish writers found their literary inspiration in the political and cultural issues surrounding their nation’s quest for independence from Great Britain, Lewis found his primarily in the landscapes of Ireland. These, he declared, had inspired and shaped the prose and poetry of many before him—perhaps most important, Edmund Spenser’s classic The Faerie Queene, an Elizabethan work that Lewis regularly expounded in his lectures at Oxford and Cambridge. For Lewis, this classic work of “quests and wanderings and inextinguishable desires” clearly reflected Spenser’s many years spent in Ireland. Who could fail to detect “the soft, wet air, the loneliness, the muffled shapes of the hills” or “the heart-rending sunsets” of Ireland? For Lewis—who here identifies himself as someone who actually is “an Irishman”—Spenser’s subsequent period in England led to a loss of his imaginative power. “The many years in Ireland lie behind Spenser’s greatest poetry, and the few years in England behind his minor poetry.”

Lewis’s language echoes his origins. In his correspondence, Lewis regularly uses Anglo-Irish idioms or slang derived from Gaelic, without offering a translation or explanation—for example, the phrases to “make a poor mouth” (from the Gaelic an béal bocht, meaning “to complain of poverty”), or “whisht, now!” (meaning “be quiet,” derived from the Gaelic bí i do thost). Other idioms reflect local idiosyncrasies, rather than Gaelic linguistic provenance, such as the curious phrase “as long as a Lurgan spade” (meaning “looking gloomy” or “having a long face”). Although Lewis’s voice in his “broadcast talks” of the 1940s is typical of the Oxford academic culture of his day, his pronunciation of words such as friend, hour, and again betrays the subtle influence of his Belfast roots.

So why is Lewis not celebrated as one of the greatest Irish writers of all time? Why is there no entry for “Lewis, C. S.” in the 1,472 pages of the supposedly definitive Dictionary of Irish Literature (1996)? The real issue is that Lewis does not fit—and, indeed, must be said partly to have chosen not to fit—the template of Irish identity that has dominated the late twentieth century. In some ways, Lewis represents precisely the forces and influences which the advocates of a stereotypical Irish literary identity wished to reject. If Dublin stood at the centre of the demands for Home Rule and the reassertion of Irish culture in the early twentieth century, Lewis’s home city of Belfast was the heart of opposition to any such developments.

One of the reasons why Ireland has largely chosen to forget about Lewis is that he was the wrong kind of Irishman. In 1917, Lewis certainly saw himself as sympathetic to the “New Ireland School,” and was considering sending his poetry to Maunsel and Roberts, a Dublin publisher with strong links to Irish nationalism, having published the collected works of the great nationalist writer Patrick Pearse (1879–1916) that same year. Conceding that they were “only a second-rate house,” Lewis expressed the hope that this might mean they would take his submission seriously.

Yet a year later, things seemed very different to Lewis. Writing to his longtime friend Arthur Greeves, Lewis expressed his fear that the New Ireland School would end up as little more than “a sort of little by-way of the intellectual world, off the main track.” Lewis now recognised the importance of keeping “in the broad highway of thought,” writing for a broad readership rather than one narrowly defined by certain cultural and political agendas. To be published by Maunsel would, Lewis declared, be tantamount to associating himself with what was little more than a “cult.” His Irish identity, inspired by Ireland’s landscape rather than its political history, would find its expression in the literary mainstream, not one of its “side-tracks.” Lewis may have chosen to rise above the provinciality of Irish literature; he nevertheless remains one of its most luminous and famous representatives.

Surrounded by Books: Hints of a Literary Vocation

The physical landscape of Ireland was unquestionably one of the influences that shaped Lewis’s fertile imagination. Yet there is another source which did much to inspire his youthful outlook—literature itself. One of Lewis’s most persistent memories of his youth is that of a home packed with books. Albert Lewis might have worked as a police solicitor to earn his keep, but his heart lay in the reading of literature.

In April 1905, the Lewis family moved to a new and more spacious home that had just been constructed on the outskirts of the city of Belfast—“Leeborough House” on the Circular Road in Strandtown, known more informally as “Little Lea” or “Leaboro.” The Lewis brothers were free to roam this vast house, and allowed their imaginations to transform it into mysterious kingdoms and strange lands. Both brothers inhabited imaginary worlds, and committed something of these to writing. Lewis wrote about talking animals in “Animal-Land,” while Warnie wrote about “India” (later combined into the equally imaginary land of Boxen).

As Lewis later recalled, wherever he looked in this new house, he saw stacks, piles, and shelves of books. On many rainy days, he found solace and company in reading these works and roaming freely across imagined literary landscapes. The books so liberally scattered throughout the “New House” included works of romance and mythology, which opened the windows of Lewis’s young imagination. The physical landscape of County Down was seen through a literary lens, becoming a gateway to distant realms. Warren Lewis later reflected on the imaginative stimulus offered to him and his brother by wet weather and a sense of longing for something more satisfying. Might his brother’s imaginative wanderings have been prompted by his childhood “staring out to unattainable hills,” seen through rain and under grey skies?

1.3 The Lewis family at Little Lea in 1905. Back Row (left to right): Agnes Lewis (aunt), two maids, Flora Lewis (mother). Front Row (left to right): Warnie, C. S. Lewis, Leonard Lewis (cousin), Eileen Lewis (cousin), and Albert Lewis (father), holding Nero (dog).

Ireland is the “Emerald Isle” precisely on account of its high levels of rainfall and mist, which ensure moist soils and lush green grass. It was natural for Lewis to later transfer this sense of confinement by rain to four young children, trapped in an elderly professor’s house, unable to explore outside because of a “steady rain falling, so thick that when you looked out of the window you could see neither the mountains nor the woods nor even the stream in the garden.” Is the professor’s house in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe modelled on Leeborough?

From Little Lea, the young Lewis could see the distant Castlereagh Hills, which seemed to speak to him of something of heartrending significance, lying tantalizingly beyond his reach. They became a symbol of liminality, of standing on the threshold of a new, deeper, and more satisfying way of thinking and living. An unutterable sense of intense longing arose within him as he contemplated them. He could not say exactly what it was that he longed for, merely that there was a sense of emptiness within him, which the mysterious hills seemed to heighten without satisfying. In The Pilgrim’s Regress (1933), these hills reappear as a symbol of the heart’s unknown desire. But if Lewis was standing on the threshold of something wondrous and enticing, how could he enter this mysterious realm? Who would open the door and allow him through? Perhaps unsurprisingly, the image of a door became increasingly significant to Lewis’s later reflections on the deeper questions of life.

The low, green line of the Castlereagh Hills, though actually quite close, thus came to be a symbol of something distant and unattainable. These hills were, for Lewis, distant objects of desire, marking the end of his known world, from which the whisper of the haunting “horns of elfland” could be heard. “They taught me longing—Sehnsucht; made me for good or ill, and before I was six years old, a votary of the Blue Flower.”

We must linger over this statement. What does Lewis mean by Sehnsucht? The German word is rich with emotional and imaginative associations, famously described by the poet Matthew Arnold as a “wistful, soft, tearful longing.” And what of the “Blue Flower”? Leading German Romantic writers, such as Novalis (1772–1801) and Joseph von Eichendorff (1788–1857), used the image of a “Blue Flower” as a symbol of the wanderings and yearnings of the human soul, especially as this sense of longing is evoked—though not satisfied—by the natural world.

Even at this early stage, then, Lewis was probing and questioning the limits of his world. What lay beyond its horizons? Yet Lewis could not answer the questions that these longings so provocatively raised in his youthful mind. To what did they point? Was there a doorway? And if so, where was it to be found? And what did it lead to? Finding answers to these questions would preoccupy Lewis for the next twenty-five years.

Solitude: Warnie Goes to England

Everything we know about Lewis around 1905 suggests a lonely, introverted boy with hardly any friends, who found pleasure and fulfilment in the solitary reading of books. Why solitary? Having secured a new house for his family, Albert Lewis now turned his attention to ensuring the future prospects of his sons. As a pillar of the Protestant establishment in Belfast, Albert Lewis took the view that the interests of his sons would be best advanced by sending the boys to boarding school in England. Albert’s brother William had already sent his son to an English school, seeing this as an acceptable route to social advancement. Albert decided to do the same, and took professional advice about which school would best suit his needs.

The London educational agents Gabbitas & Thring had been founded in 1873 to recruit suitable schoolmasters for leading English schools and provide guidance for parents wanting to secure the best possible education for their children. Schoolmasters whom they helped to find suitable positions included such future stars—now, it must be said, not chiefly remembered for having ever been schoolmasters—as W. H. Auden, John Betjeman, Edward Elgar, Evelyn Waugh, and H. G. Wells. By 1923, when the firm celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of its founding, over 120,000 teaching vacancies had been negotiated and no fewer than 50,000 parents had sought their counsel on the best school for their children. This included Albert Lewis, who asked their advice on where to send his elder son, Warren.

Their recommendation duly came through. It turned out to be stunningly bad advice. In May 1905, without making the more critical and thorough inquiries some would have expected of a man in his position, Albert Lewis packed the nine-year-old Warren off to Wynyard School in Watford, north of London. It was perhaps the first of many mistakes that Lewis’s father would make concerning his relationship with his sons.

Jacks—as Lewis now preferred to be called—and his brother, Warnie, had lived together in Little Lea for only a month, sharing a “Little End Room” in the top floor of the rambling house as their haven. Now, they were separated. C. S. Lewis remained at home, and was taught privately by his mother and a governess, Annie Harper. But perhaps his best teachers were the burgeoning stacks of books, none of which were forbidden to him.

For two years, the solitary Lewis roamed the large house’s long, creaking corridors and roomy attics, with vast quantities of books as his companions. Lewis’s inner world began to take shape. Where other boys of his age were playing games on the streets or in the countryside around Belfast, Lewis constructed, inhabited, and explored his own private worlds. He was forced to become a loner—something that unquestionably catalysed his imaginative life. In Warnie’s absence, he had nobody as a soul mate with whom he could share his dreams and longings. The school vacations became of supreme importance to him. They were when Warnie came home.

First Encounters with Joy

At some point around this time, Lewis’s already rich imaginative life took a new turn. Lewis later recalled three early experiences which he regarded as shaping one of his life’s chief concerns. The first of these took place when the fragrance of a “flowering currant bush” in the garden at Little Lea triggered a memory of his time in the “Old House”—Dundela Villas, which Albert Lewis had then rented from a relative. Lewis speaks of experiencing a transitory, delectable sense of desire, which overwhelmed him. Before he had worked out what was happening, the experience had passed, leaving him “longing for the longing that had just ceased.” It seemed to Lewis to be of enormous importance. “Everything else that had ever happened to me was insignificant in comparison.” But what did it mean?

The second experience came when reading Beatrix Potter’s Squirrel Nutkin (1903). Though Lewis admired Potter’s books in general at this time, something about this work sparked an intense longing for something he clearly struggled to describe—“the Idea of Autumn.” Once more, Lewis experienced the same intoxicating sense of “intense desire.”

The third came when he read Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s translation of a few lines from the Swedish poet Esaias Tegnér (1782–1846):

I heard a voice that cried,

Balder the beautiful

Is dead, is dead—

Lewis found the impact of these words devastating. It was as if they opened a door that he did not know existed, allowing him to see a new realm beyond his own experience, which he longed to enter and possess. For a moment, nothing else seemed to matter. “I knew nothing of Balder,” he recalled, “but instantly I was uplifted into huge regions of northern sky, [and] I desired with almost sickening intensity something never to be described (except that it is cold, spacious, severe, pale, and remote).” Yet even before Lewis had realised what was happening to him, the experience passed, and left him longing to be able to reenter it.

Looking back on these three experiences, Lewis understood that they could be seen as aspects or manifestations of the same thing: “an unsatisfied desire which is itself more desirable than any other satisfaction. I call it Joy.” The quest for that Joy would become a central theme of Lewis’s life and writing.

So how are we to make sense of these experiences, which played such a significant role in Lewis’s development, especially the shaping of his “inner life”? Perhaps we can draw on the classic study The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), in which the Harvard psychologist William James (1842–1910) tried to make sense of the complex, powerful experiences that lay at the heart of the lives of so many religious thinkers. Drawing extensively on a wide range of published writings and personal testimonies, James identified four characteristic features of such experiences. In the first place, such experiences are “ineffable.” They defy expression, and cannot be described adequately in words.

In the second place, James suggests that those who experience them achieve “insight into depths of truth unplumbed by the discursive intellect.” In other words, they are experienced as “illuminations, revelations, full of significance and importance.” They evoke an “enormous sense of inner authority and illumination,” transfiguring the understanding of those who experience them, often evoking a deep sense “of being revelations of new depths of truth.” These themes clearly underlie Lewis’s early desriptions of “Joy,” such as his statement that “everything else that had ever happened to me was insignificant in comparison.”

Third, James goes on to emphasise that these experiences are transient; they “cannot be sustained for long.” Usually they last from a few seconds to just minutes, and their quality cannot be accurately remembered, though the experience is recognised if it recurs. “When faded, their quality can but imperfectly be reproduced in memory.” This aspect of James’s typology of religious experience is clearly reflected in Lewis’s prose.

Finally, James suggests that those who have had such an experience feel as if they have been “grasped and held by a superior power.” Such experiences are not created by active subjects; they come upon people, often with overwhelming power.

Lewis’s eloquent descriptions of his experience of “Joy” clearly fit into James’s characterisation. Lewis’s experiences were perceived as deeply meaningful, throwing open the doors of another world, which then shut almost immediately, leaving him exhilarated at what had happened, yet longing to recover it. They are like momentary and transient epiphanies, when things suddenly seem to come acutely and sharply into focus, only for the light to fade and the vision to recede, leaving nothing but a memory and a longing.

Lewis was left with a sense of loss, even of betrayal, in the aftermath of such experiences. Yet as frustrating and disconcerting as they may have been, they suggested to him that the visible world might be only a curtain that concealed vast, uncharted realms of mysterious oceans and islands. It was an idea that, once planted, never lost its imaginative appeal or its emotional power. Yet, as we shall see, Lewis would soon come to believe it was illusory, a childhood dream which the dawning of adult rationality exposed as a cruel delusion. Ideas of a transcendent realm or of a God might be “lies breathed through silver,” but they remained lies nevertheless.

The Death of Flora Lewis

Edward VII came to the English throne after the death of Victoria in 1901 and reigned until 1910. The Edwardian Age is now often seen as a golden period of long summer afternoons and elegant garden parties, an image which was shattered by the Great War of 1914–1918. While this highly romanticised view of the Edwardian Age largely reflects the postwar nostalgia of the 1920s, there is no doubt that many at the time saw it as a settled and secure age. There were troubling developments afoot—above all, the growing military and industrial power of Germany and the economic strength of the United States, which some realised posed significant threats to British imperial interests. Yet the dominant mood was that of an empire which was settled and strong, its trade routes protected by the greatest navy the world had ever known.

This sense of stability is evident in Lewis’s early childhood. In May 1907, Lewis wrote to Warnie, telling him that it was nearly settled that they were going to spend part of their holidays in France. Going abroad was a significant departure for the Lewis family, who normally spent up to six weeks during the summer at northern Irish resorts such as Castlerock or Portrush. Their father, preoccupied with his legal practice, was often an intermittent presence on these occasions. As things turned out, he would not join them in France at all.

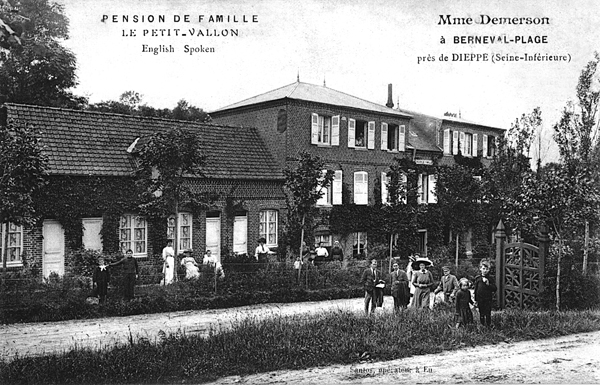

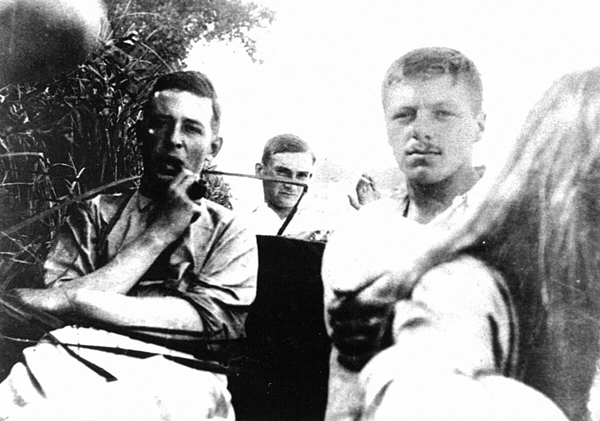

1.4 Pension le Petit Vallon, Berneval-le-Grand, Pas-de-Calais, France. Postcard dating from around 1905.

In the event, Lewis enjoyed an intimate and tranquil holiday with his brother and mother. On 20 August 1907, Flora Lewis took her two sons to the Pension le Petit Vallon, a family hotel in the small town of Berneval-le-Grand in Normandy, not far from Dieppe, where they would remain until 18 September. A picture postcard of the early 1900s perhaps helps us understand Flora’s choice: the reassuring words “English spoken” feature prominently above a photograph of Edwardian families relaxing happily on its grounds. Any hopes that Lewis had of learning some French were dashed when he discovered that all the other guests were English.

It was to be an idyllic summer of the late Edwardian period, with no hints of the horrors to come. When hospitalised in France during the Great War a mere eighteen miles (29 kilometres) east of Berneval-le-Grand, Lewis found himself wistfully recalling those precious, lost golden days. Nobody had foreseen the political possibility of such a war, nor the destruction it would wreak—just as nobody in the Lewis family could have known that this would be the last holiday they would spend together. A year later, Flora Lewis was dead.

Early in 1908, it became clear that Flora was seriously ill. She had developed abdominal cancer. Albert Lewis asked his father, Richard, who had been living in Little Lea for some months, to move out. They needed the space for the nurses who would attend Flora. It was too much for Richard Lewis. He suffered a stroke in late March, and died the following month.

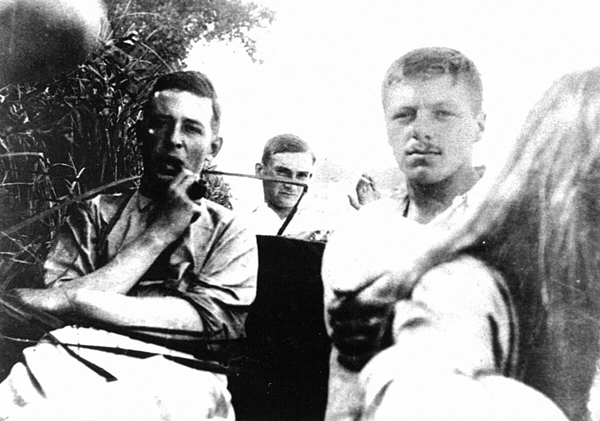

When it became clear that Flora was in terminal decline, Warnie was summoned home from school in England to be with his mother in her final weeks. Their mother’s illness brought the Lewis brothers even closer together. One of the most touching photographs of this period shows Warnie and C. S. Lewis standing by their bicycles, outside Glenmachan House, close to Little Lea, early in August 1908. Lewis’s world was about to change, drastically and irreversibly.

Flora died in her bed at home on 23 August 1908—Albert Lewis’s forty-fifth birthday. The somewhat funereal quotation for that day on her bedroom calendar was from Shakespeare’s King Lear: “Men must endure their going hence.” For the rest of Albert Lewis’s life, Warnie later discovered, the calendar remained open at that page.

1.5 Lewis and Warnie with their bicycles in front of the Ewart family home, Glenmachan House, in August 1908.

Following the custom of the day, Lewis was obliged to view the dead body of his mother lying in an open coffin, the gruesome marks of her illness all too visible. It was a traumatic experience for him. “With my mother’s death all settled happiness, all that was tranquil and reliable, disappeared from my life.”

In The Magician’s Nephew, Digory Kirke’s mother is lovingly described on her deathbed, in terms that seem to echo Lewis’s haunting memories of Flora: “There she lay, as he had seen her lie so many other times, propped up on the pillows, with a thin, pale face that would make you cry to look at.” There is little doubt that this passage recalls Lewis’s own distress at the death of his mother, especially the sight of her emaciated body in an open coffin. In allowing Digory’s mother to be cured of her terminal illness by the magic apple from Narnia, Lewis seems to be healing his own deep emotional wounds with an imaginative balm, trying to deal with what really happened by imagining what might have happened.

While Lewis was clearly distressed at his mother’s death, his memories of this dark period often focus more on its broader implications for his family. As Albert Lewis tried to come to terms with his wife’s illness, he seems to have lost an awareness of the deeper needs of his sons. C. S. Lewis depicts this period as heralding the end of his family life, as the seeds of alienation were sown. Having lost his wife, Albert Lewis was in danger of losing his sons as well. Two weeks after Flora’s death, Albert’s elder brother, Joseph, died. The Lewis family, it seemed, was in crisis. The father and his two sons were on their own. “It was sea and islands now; the great continent had sunk like Atlantis.”

This could have been a time for the rebuilding of paternal affection and rekindling of filial devotion. Nothing of the sort happened. That Albert’s judgement failed him at this critical time is made abundantly clear in his decision concerning the future of his sons at this crisis in their young lives. A mere two weeks after the traumatic death of his mother, C. S. Lewis found himself standing on the Belfast quayside with Warnie, preparing to board the overnight steamer to the Lancashire port of Fleetwood. An emotionally unintelligent father bade his emotionally neglected sons an emotionally inadequate farewell. Everything that gave the young Lewis his security and identity seemed to be vanishing around him. Lewis was being sent away from Ireland—from his home and from his books—to a strange place where he would live among strangers, with his brother, Warnie, as his only companion. He was being sent to Wynyard School—the “Belsen” of Surprised by Joy.

CHAPTER 2

1908–1917

The Ugly Country of England: Schooldays

In 1962, Francine Smithline—a schoolgirl from New York—wrote to C. S. Lewis, telling him how much she had enjoyed his Narnia books and asking him for information about his own schooldays. In reply, Lewis informed her that he had attended three boarding schools, “of which two were very horrid.” In fact, Lewis continues, he “never hated anything as much, not even the front line trenches in World War I.” Even the most casual reader of Surprised by Joy is struck by both the vehemence of Lewis’s hatred for the schools he attended in England and the implausibility that they were worse than the death-laden trenches of the Great War.

One of the significant sources of tension between C. S. Lewis and his brother in the late 1950s was Warnie’s belief that Lewis had significantly misrepresented his time at Malvern College in Surprised by Joy (1955). George Sayer (1914–2005), a close friend who penned one of the most revealing and perceptive biographies of Lewis, recalls Lewis admitting later in life that his account of his time at Malvern was “lies,” reflecting the complex interaction of two strands of his identity at that time. Sayer’s recollection leaves readers of Surprised by Joy wondering about both the extent and motivation of Lewis’s reconstruction of his past.

Perhaps Lewis’s judgement here may have been clouded by his overwhelmingly negative initial impressions of England, which spilled over into his educational experience. As he later remarked, he “conceived a hatred for England which took many years to heal.” His aversion to English schools possibly reflects a deeper cultural dislike of England itself at this time, evident in some of his correspondence. In June 1914, for example, Lewis complained about being “cooped up in this hot, ugly country of England” when he could have been roaming the cool, lush countryside of County Down.

Yet there is clearly something deeper and more visceral here. Lewis simply does not seem to have fitted in to the public school culture of the Edwardian Age. What others saw as a necessary, if occasionally distasteful, preparation for the rigours of life in the real world was dismissed and vilified by Lewis as a “concentration camp.” What his father hoped would make him into a successful citizen came close to breaking him instead.

Lewis’s experience of British schools, following the death of his mother, can be summarised as follows:

- Wynyard School, Watford (“Belsen”): September 1908–June 1910

- Campbell College, Belfast: September–December 1910

- Cherbourg School, Malvern (“Chartres”): January 1911–June 1913

- Malvern College (“Wyvern”): September 1913–June 1914

- Private tuition at Great Bookham: September 1914–March 1917

The three English schools to which Lewis took exception are presumably those he chose to identify by pseudonyms: Wynyard School, Cherbourg School, and Malvern College. As we shall see, his memories of his time at Great Bookham were much more positive, as was his view of its impact on the shaping of his mind.

Wynyard School, Watford: 1908–1910

Lewis’s first educational experience in England was at Wynyard School, a converted pair of dreary yellow-brick houses on Langley Road, Watford. This small private boarding school had been established by Robert “Oldie” Capron in 1881, and appears to have enjoyed some small success in its early years. By the time Lewis arrived, however, it had fallen on hard times, having only about eight or nine boarders, and about the same number of “day-boys.” His brother had already studied there for two years, and had adjusted to its brutal regime with relative ease. Lewis, with little experience of the world outside the gentle cocoon of Little Lea, was shocked by Capron’s brutality, and later dubbed the school “Belsen” after the infamous Nazi concentration camp.

While initially hoping that things would work out well, Lewis rapidly came to hate Wynyard, and regarded his period there as an almost total waste of time. Warnie left Wynyard in the summer of 1909 and went on to Malvern College, leaving his younger brother alone to cope with an institution that was clearly in terminal decline. Lewis recalled his education at Wynyard as the forced feeding and rote learning of “a jungle of dates, battles, exports, imports and the like, forgotten as soon as learned and perfectly useless had they been remembered.” Warnie concurred in this judgement: “I cannot remember one single piece of instruction that was imparted to me at Wynyard.” Nor was there any library by which Lewis might nourish the imaginative side of his life. In the end, the school was closed down in the summer of 1910 when Capron was finally certified as being insane.

Albert Lewis was now forced to review his arrangements for his younger son’s education. While Warnie went off to resume his education at Malvern College, Lewis was sent to Campbell College, a boarding school in the city of Belfast, only a mile from Little Lea. As Lewis later remarked, Campbell had been founded to allow “Ulster boys all the advantages of a public-school education without the trouble of crossing the Irish Sea.” It is not clear whether his father intended this to be a permanent arrangement. In the event, Lewis developed a serious respiratory illness while at Campbell, and his father reluctantly withdrew him. It was not an unhappy time for Lewis. Indeed, Lewis seems to have wished that the arrangement could have been continued. His father, however, had other plans. Unfortunately, they turned out not to be very good.

Cherbourg School, Malvern: 1911–1913

After further consultation with Gabbitas & Thring, Lewis was sent to Cherbourg School (“Chartres” in Surprised by Joy) in the English Victorian spa town of Great Malvern. During the nineteenth century, Malvern became popular as a hydrotherapy spa on account of its spring waters. As spa tourism declined towards the end of the century, many former hotels and villas were converted to small boarding schools, such as Cherbourg. This small preparatory school, which had about twenty boys between the ages of eight and twelve during Lewis’s time, was located next to Malvern College, where Warnie was already ensconced as a student. The two brothers would at least be able to see each other once more.

The most important outcome of Lewis’s time at Cherbourg was that he won a scholarship to Malvern College. Yet Lewis recalls a number of developments in his inner life to which his schooling at Cherbourg was essentially a backdrop, rather than a cause or stimulus. One of the most important was his discovery of what he termed “Northernness,” which took place “fairly early” during his time at Cherbourg. Lewis regarded this discovery as utterly and gloriously transformative, comparable to a silent and barren Arctic icescape turning into “a landscape of grass and primroses and orchards in bloom, deafened with bird songs and astir with running water.”

Lewis’s recollections of this development are as imaginatively precise as they are chronologically vague. “I can lay my hand on the very moment; there is hardly any fact I know so well, though I cannot date it.” The stimulus was a “literary periodical” which had been left lying around in the schoolroom. This can be identified as the Christmas edition of The Bookman, published in December 1911. This magazine included a coloured supplement reproducing some of Arthur Rackham’s suite of thirty illustrations to an English translation by Margaret Armour of the libretto of Richard Wagner’s operas Siegfried and The Twilight of the Gods, which had been published earlier that year.

Rackham’s highly evocative illustrations proved to be a powerful imaginative stimulus to Lewis, causing him to be overwhelmed by an experience of desire. He was engulfed by “pure ‘Northernness’”—by “a vision of huge, clear spaces hanging above the Atlantic in the endless twilight of Northern summer.” Lewis was thrilled to be able to experience again something that he had believed he had permanently lost. This was no “wish fulfilment and fantasy”; this was a vision of standing on the threshold of another world, and peering within. Hoping to recapture something of this sense of wonder, Lewis indulged his growing passion in Wagner, spending his pocket money on recordings of Wagner’s operas, and even managing to buy a copy of the original text from which the Rackham illustrations had been extracted.

Although Lewis’s letters of his Malvern period probably conceal as much as they reveal, they nevertheless hint of some of the themes that would recur throughout his career. One of those is Lewis’s sense of being an Irishman in exile in a strange land. Lewis had not simply lost his paradise; he had been expelled from his Eden. Lewis might live in England; he did not, however, see himself as English. Even in his final days at Cherbourg, Lewis had become increasingly aware of having been “born in a race rich in literary feeling and mastery of their own tongue.” In the 1930s, Lewis found the physical geography of his native Ireland to be a stimulus to his own literary imagination, and that of others—such as the poet Edmund Spenser. The seeds of this development can be seen in his letters home in 1913.

A significant intellectual development which Lewis attributes to this period in his life was his explicit loss of any remnants of a Christian faith. Lewis’s account of this final erosion of faith in Surprised by Joy is less satisfactory than one might like, particularly given the importance of faith in his later life. While unable to give “an accurate chronology” of his “slow apostasy,” Lewis nevertheless identifies a number of factors that moved him in that direction.

Perhaps the most important of these, as judged by its lingering presence in his subsequent writings, was raised by his reading of Virgil and other classical authors. Lewis noted that their religious ideas were treated by both scholars and teachers as “sheer illusion.” So what of today’s religious ideas? Were they not simply modern illusions, the contemporary counterpart to their ancient forebears? Lewis came to the view that religion, though “utterly false,” was a natural development, “a kind of endemic nonsense into which humanity tended to blunder.” Christianity was just one of a thousand religions, all claiming to be true. So why should he believe this one to be right, and the others wrong?

By the spring of 1913, Lewis had decided where he wished to go after Cherbourg. In a letter to his father of June 1913, he declares his time at Cherbourg—though initially something of a “leap in the dark”—to have been a “success.” He liked Great Malvern as a town, and would like to proceed to “the Coll.”—in other words, to Malvern College, where he could join his older brother, Warnie. In late May, Warnie announced that he wanted to pursue a military career, and would spend the autumn of 1913 at Malvern College, preparing for the entrance examination at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst.

However, things did not work out quite as expected. In June, Lewis won a scholarship to Malvern College beginning in September, despite being ill and having to take the examination in Cherbourg’s sickroom. But Warnie would no longer be there. He had been asked to leave by the headmaster after being caught smoking on school premises. (Both Lewis brothers had developed their lifelong habit of smoking by this stage.) Albert Lewis now had to work out how to prepare Warnie for the Sandhurst entrance examinations without any assistance from the masters of Malvern College. He found an answer—a brilliant answer, that would have significant and positive implications for his younger son a year later.

Albert Lewis had been a pupil at Lurgan College in Ireland’s County Armagh from 1877–1879, and had developed a great respect for his former headmaster, William Thompson Kirkpatrick (1848–1921). Kirkpatrick had arrived at Lurgan College in 1876, at which time it had only sixteen pupils. A decade later, it was regarded as one of the premier schools in Ireland. Kirkpatrick retired in 1899, and moved with his wife to Sharston House in Northenden, Cheshire, to be near their son, George, who was then working for Browett, Lindley & Co., Engine Makers of Patricroft, Manchester. However, it seems that Kirkpatrick’s wife had little enthusiasm for the industrialised Northwest of England, and the couple soon moved to Great Bookham in the “Stockbroker Belt” of the southern county of Surrey, where Kirkpatrick set himself up as a private tutor.

Albert Lewis acted as Kirkpatrick’s solicitor, and the two had occasion to correspond over what should be done with parents who refused to pay their sons’ school fees. Albert Lewis had asked Kirkpatrick’s advice on educational matters in the past, and he now asked for something more specific and personal: would Kirkpatrick prepare Warnie for the entrance examination to Sandhurst? The deal was done, and Warnie began his studies at Great Bookham on 10 September 1913. Eight days later, his younger brother started at Malvern College—the “Wyvern” of Surprised by Joy—without his older brother as his mentor and friend. Lewis was on his own.

Malvern College: 1913–1914

Lewis presents Malvern College as a disaster. Surprised by Joy devotes three of its fifteen chapters to railing against his experiences at “the Coll,” faulting it at point after point. Yet this accumulation of Lewis’s vivid and harsh memories curiously fails to advance his narrative of the pursuit of Joy. Why spend so much time recounting such painful and subjective memories, which others who knew the college at that time (including Warnie) criticised as distorted and unrepresentative? Perhaps Lewis saw the writing of these sections of Surprised by Joy as a cathartic exercise, allowing him to purge his painful memories by writing about them at greater length than required. Yet even a sympathetic reader of this work cannot fail to see that the pace of the book slackens in the three chapters devoted to Malvern, where the narrative detail obscures the plotline.

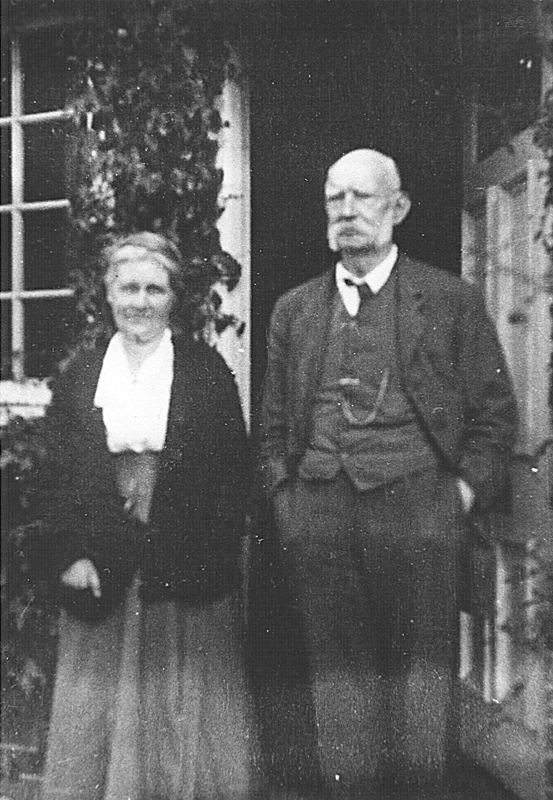

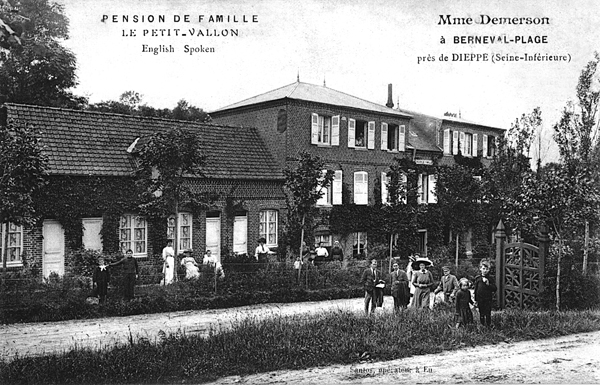

2.1 William Thompson Kirkpatrick (1848–1921), at his home in Great Bookham in 1920, photographed by Warren Lewis during his visit when on leave from the British army. This is the only known photograph of Kirkpatrick.

Lewis declares that he became a victim of the “fagging” system, by which younger pupils were expected to act as errand boys for the older pupils (the “Bloods”). The more a boy was disliked by his peers and elders, the more he would be picked on and exploited in this way. This was customary in English public schools of this age. What most boys accepted as part of a traditional initiation rite into adulthood was seen by Lewis as a form of forced labour. Lewis suggested that the forms of service that younger boys were expected to provide to their seniors were rumoured (but never proved) to include sexual favours—something which Lewis found horrifying.

Perhaps more significantly, Lewis found himself excluded from the value system of Malvern College, which was heavily influenced by the then dominant educational philosophy of the English public school system—athleticism. By the end of the Edwardian era, the “games cult” had assumed an almost unassailable position as the centrepiece of an English public school education. Athleticism was an ideology with a darker side. Boys who were not good at games were ridiculed and bullied by their peers. Athleticism devalued intellectual and artistic achievement and turned many schools into little more than training camps for the glorification of physicality. Yet the cultivation of “manliness” was seen as integral to the development of “character”—an essential trait that dominated the educational theories of this period in British culture. In all these respects, Malvern was typical of the Edwardian age. It provided what it believed was needed, and what parents clearly wanted.

But it was not what Lewis wanted. His “native clumsiness,” partly arising from having only one joint in his thumbs, made excelling in anything physical a total impossibility. Lewis seems to have made little attempt to fit into the school’s culture. His refusal to conform simply created the impression that Lewis was socially withdrawn and academically arrogant. As Lewis wryly remarked in a letter, Malvern helped him discover what he did not want to be: “If I had never seen the horrible spectacle which these coarse, brainless English schoolboys present, there might be a danger of my sometimes becoming like that myself.” To many, these remarks simply sound arrogant and condescending. Yet Lewis was clear that one of Malvern’s relatively few positive achievements was to help him realise that he was arrogant. It was an aspect of his character that he would have to deal with in the coming years.

Lewis frequently sought refuge in the school library, finding solace in books. He also developed a friendship with the classics master, Harry Wakelyn Smith (“Smewgy”). Smith worked with Lewis on his Latin and helped him begin his serious study of Greek. Perhaps more important, he taught Lewis how to analyse poetry properly, allowing its aesthetic qualities to be appreciated. Furthermore, he helped Lewis realise that poetry was to be read in such a way that its rhythm and musical qualities could be appreciated. Lewis later expressed his gratitude in a poem explaining how Smith—an “old man with a honey-sweet and singing voice”—taught him to love the “Mediterranean metres” of classical poetry.

Important though such positive encounters may have been for Lewis’s later scholarly and critical development, at the time they were ultimately intellectual diversions, designed to take Lewis’s mind off what he regarded as an insufferable school culture. Warnie took the view that his brother was simply a “square peg in a round hole.” With the benefit of hindsight, he believed that Lewis ought not to have been sent to a public school at all. Lewis’s lack of athletic prowess and his strong intellectual leanings immediately identified him as a “misfit, a heretic, an object of suspicion within the collective-minded and standardizing Public School system.” But at the time, Warnie was clear that the fault, if fault there were, lay in Lewis himself, not in the school.

It remains unclear why Lewis spends so much of Surprised by Joy dealing with his time at Malvern. It is true that he was invited to be a governor of the college in 1929, an invitation which caused him some amusement. Yet there is no doubt of Lewis’s despair at the time concerning his circumstances there, and his desperate attempts to persuade his father to move him to a more congenial place. “Please take me out of this as soon as possible,” he wrote imploringly to his father in March 1914, as he prepared to return to Belfast for the school holidays.

Albert Lewis finally realised things were not working out for his younger son. He consulted with Warnie, who was by then in his second month of training as a British army officer at Sandhurst. Warnie took the view that his younger brother had contributed significantly to his own deteriorating situation. He had hoped, he told his father, that Malvern would provide his brother with the same “happy years and memories and friendships that he would carry with him to the grave.” But it hadn’t worked out like that. Lewis had made Malvern “too hot to hold him.” A radical rethink was required. Since Warnie had benefitted from personal tuition from Kirkpatrick, Lewis should be offered the same. It is not difficult to discern Warnie’s irritation with his brother when he tells his father that “he could amuse himself by detonating his cheap little stock of intellectual fireworks under old K[irkpatrick]’s nose.”

Albert Lewis then wrote to Kirkpatrick, asking him for his advice. Kirkpatrick initially suggested that Lewis should resume his studies at Campbell College. But as the two men wrestled with the problem, another solution began to emerge. Albert persuaded Kirkpatrick to become Lewis’s personal tutor effective September 1914. Kirkpatrick professed himself overwhelmed by this compliment: “To have been the teacher of the father and his two sons is surely a unique experience.” It was still risky. Warnie had loved Malvern, yet Lewis had detested it. What would Lewis make of Kirkpatrick, who had been so good for Warnie? Kirkpatrick’s efforts had led to Warnie’s being ranked twenty-second out of more than two hundred successful candidates in the highly competitive entrance examination. Warnie’s military record shows that he entered Sandhurst on 4 February 1914 as a “Gentleman Cadet,” being awarded a “Prize Cadetship with emoluments.” His military career was off to a flying start.

Meanwhile, Lewis had returned home to Belfast for the vacation. In mid-April 1914, shortly before he was due to return for his final term at Malvern College, he received a message. Arthur Greeves (1895–1966) was in bed recovering from an illness and would welcome a visit. Greeves, who was the same age as Warnie, was the youngest son of Joseph Greeves, one of Belfast’s most wealthy flax-spinners. The family lived at “Bernagh,” a large house just over the road from Little Lea.

2.2 A tennis party at Glenmachan House, the Ewart family home, close to Little Lea, in the summer of 1910. Arthur Greeves is on the far left in the back row, with C. S. Lewis to the far right. Lily Greeves, Arthur’s sister, is seated second from the right, in front of Lewis

In Surprised by Joy, Lewis recalls that Greeves had been trying to initiate a friendship with him for some time, but that they had never met. Yet there is evidence that Lewis’s memory may not be entirely correct here. In one of his earliest surviving letters of May 1907, Lewis informed Warnie that a telephone had just been installed at Little Lea. He had used this new piece of technology to call Arthur Greeves, but had not been able to speak to him. This hints at a childhood acquaintance of some sort. If Lewis and Greeves had been friends around this time, it seems likely that Lewis’s enforced absence from Belfast at English schools had caused the existing relationship to wither.

Lewis agreed to visit Greeves with some reluctance. He found him sitting up in bed, with a book beside him: H. M. A. Guerber’s Myths of the Norsemen (1908). Lewis, whose love of “Northernness” now knew few bounds, looked at the book in astonishment: “Do you like that?” he asked—only to receive the same excited reply from Greeves. Lewis had finally found a soul mate. They would remain in touch regularly until Lewis’s death, nearly fifty years later.

As his final term at Malvern drew to an end, Lewis wrote his first letter to Greeves, planning a walk together. Though he was “cooped up” in the “hot, ugly country of England,” they could watch the sun rise over the Holywood Hills and see Belfast Lough and Cave Hill. Yet a month later, Lewis’s view of England had changed. “Smewgy” had invited him and another boy to drive into the country, leaving behind the “flat, plain, and ugly hills of Malvern.” In their place, Lewis discovered an “enchanted ground” of “rolling hills and valleys,” with “mysterious woods and cornfields.” Perhaps England was not so bad; maybe he might stay there after all.

Bookham and the “Great Knock”: 1914–1917

On 19 September 1914, Lewis arrived at Great Bookham to begin his studies with Kirkpatrick—the “Great Knock.” Yet the world around Lewis had changed irreversibly since he had left Malvern. On 28 June, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated in Sarajevo, creating ripples of tension and instability which gradually escalated. Grand alliances were formed. If one great nation went to war, all would follow. A month later, on 28 July, Austria launched an attack against Serbia. Germany immediately launched an attack against France. It was inevitable that Britain would be drawn into the conflict. Britain eventually declared war against Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire on 4 August.

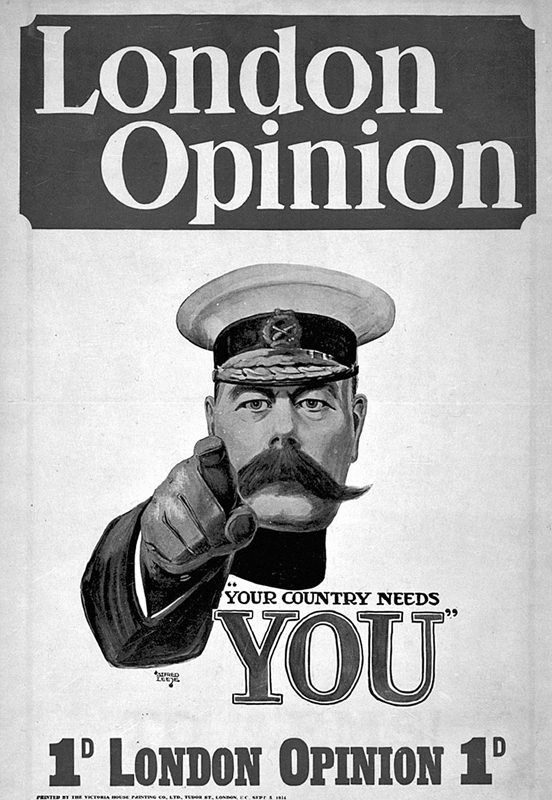

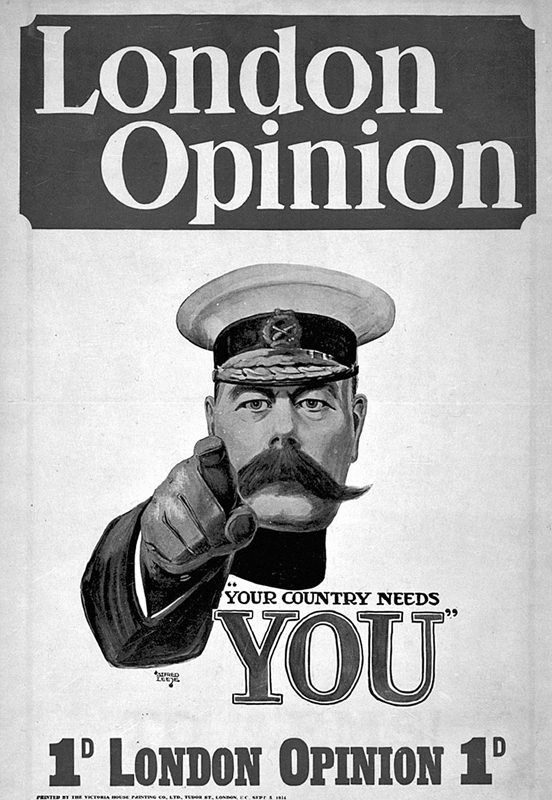

It was Warnie who was affected most immediately by this development. His period of training was reduced from eighteen months to nine, to allow him to enter active military service as soon as possible. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Royal Army Service Corps on 29 September 1914, and was on active service in France with the British Expeditionary Force by 4 November. Meanwhile, Lord Kitchener (1850–1916), Secretary of State for War, set out to organise the recruitment of the largest volunteer army that the nation had ever seen. His famous recruiting poster declaring “Your country needs you!” became one of the most familiar images of the war. Lewis could hardly have failed to feel this pressure to enlist.

2.3 “Your country needs you!” The front cover of the magazine London Opinion, published on 5 September 1914, shortly after Britain’s declaration of war. This image of Lord Kitchener, designed by the artist Alfred Leete (1882–1933), quickly achieved iconic significance, and featured prominently in British military recruitment campaigns from 1915 onwards.

While England lurched into a state of war for which it was not properly prepared, Lewis was settling in at Kirkpatrick’s house, “Gastons,” in Great Bookham. His relationship with Kirkpatrick would be of central importance, especially since his relationships with both his brother and father were by now somewhat strained and distant. Lewis travelled by steamer from Belfast to Liverpool, then by train to London. There he picked up a train from Waterloo Station to Great Bookham, where Kirkpatrick awaited him. As they walked together from the station to Kirkpatrick’s house, Lewis remarked casually, as a way of breaking the conversational ice, that the scenery in Surrey was somewhat wilder than he had anticipated.

2.4 Station Road, Great Bookham, in 1924. C. S. Lewis and Kirkpatrick would have walked along this road on their way from the railway station to Kirkpatrick’s home, Gastons.

Lewis had intended merely to begin a conversation; Kirkpatrick seized the opportunity to begin an aggressive, interactive discussion demonstrating the virtues of the Socratic method. Kirkpatrick demanded that he stop immediately. What did Lewis mean by “wildness,” and what grounds had he for not expecting it? Had he studied some maps of the area? Had he read some books about it? Had he seen photographs of the landscape? Lewis conceded he had done none of these things. His views were not based on anything. Kirkpatrick duly informed him that he had no right to have any opinion on this matter.

Some would have found this approach intimidating; others might think it to lack good manners or pastoral concern. Yet Lewis quickly realised that he was being forced to develop his critical thinking, based on evidence and reason rather than his personal intuitions. This approach was, he remarked, like “red beef and strong beer.” Lewis thrived on this diet of critical thinking.

Kirkpatrick was a remarkable man, and must be given credit for much of Lewis’s intellectual development, particularly in fostering a highly critical approach to ideas and sources. Kirkpatrick had a distinguished academic career at Queen’s College, Belfast, from which he graduated in July 1868 with First Class Honours in English, History, and Metaphysics. In his final year at Queen’s College, he had won the English Prize Essay under the nom de plume Tamerlaine. He was also awarded a Double Gold Medal by the Royal University of Ireland, the only student to gain this distinction that year. He applied unsuccessfully for the position of headmaster of Lurgan College when the college opened in 1873. There were twenty-two applications for the prestigious position. In the end, the school’s governors had to choose between Kirkpatrick and E. Vaughan Boulger of Dublin. They chose Boulger.

Undeterred, Kirkpatrick looked elsewhere for employment. He was seriously considered for the Chair of English at University College, Cork. His opportunity came, however, late in 1875, when Boulger was appointed to the Chair of Greek at University College, Cork. Kirkpatrick applied again for headmaster of Lurgan College, and was appointed to the position effective 1 January 1876. His ability to encourage and inspire his students became the substance of legend. Albert Lewis may have made many mistakes in arranging for his younger son’s education in England. But his biggest decision—based on his own judgement, rather than the flawed professional advice of Gabbitas & Thring—turned out to be his best.

Lewis’s highly condensed summary of his most significant tutors merits consideration: “Smewgy taught me Grammar and Rhetoric and Kirk taught me Dialectic.” For Lewis, he was gradually learning how to use words and develop arguments. Yet Kirkpatrick’s influence was not limited to Lewis’s dialectical skills. The old headmaster forced Lewis to learn languages, living and dead, by the simple expedient of making him use them. Two days after Lewis’s arrival, Kirkpatrick sat down with him and opened a copy of Homer’s Iliad in the original Greek. He read aloud the first twenty lines in a Belfast accent (which might have puzzled Homer), offered a translation, and invited Lewis to continue. Before long, Lewis was confident enough to read fluently in the original language. Kirkpatrick extended the approach, first to Latin, and then to living languages, including German and Italian.

To some, such educational methods will seem archaic, even ridiculous. For many students, they would have resulted in humiliating failure and loss of confidence. Lewis, however, saw them as a challenge, causing him to set his sights higher and raise his game. It was precisely the educational method that was best adapted to his abilities and his needs. In one of his most famous sermons, “The Weight of Glory” (1941), Lewis asks us to imagine a young boy who learned Greek in order to experience the joy of studying Sophocles. Lewis was that young boy, and Kirkpatrick was his teacher. In February 1917, Lewis wrote with great excitement to his father, telling him that he had been able to read the first two hundred lines of Dante’s Inferno in the original Italian “with much success.”

Yet there were other outcomes of Kirkpatrick’s rationalism that Lewis was less keen to share with his father. One of them was his increasing commitment to atheism. Lewis was clear that his atheism was “fully formed” before he went to Bookham; Kirkpatrick’s contribution was to provide him with additional arguments for his position. In December 1914, Lewis was confirmed at St. Mark’s, Dundela, the church where he had been baptised in January 1899. His relationship with his father was so poor that he felt unable to tell him that he did not wish to go through with the service, having ceased to believe in God. Lewis later used Kirkpatrick as the model for the character of MacPhee, who appears in That Hideous Strength—an articulate, intelligent, and highly opinionated Scots-Irishman, with distinctly skeptical views on matters of religious belief.

Was Lewis inclined to agree with Kirkpatrick on this matter? The only person to whom Lewis appears to have felt able to open his heart regarding his religious beliefs was Arthur Greeves, who had by now completely displaced Warnie as Lewis’s soul mate and confidant. In October 1916, Lewis provided Greeves with a full statement of his (lack of) religious beliefs. “I believe in no religion.” All religions, he wrote, are simply mythologies invented by human beings, usually in response to natural events or emotional needs. This, he declared, “is the recognised scientific account of the growth of religions.” Religion was irrelevant to questions of morality.

This letter stimulated an intense debate with Greeves, who was then both a committed and reflective Christian. They exchanged at least six letters on the topic in a period of less than a month, before declaring that their views were so far apart that there was little point in continuing the discussion. Lewis later recalled that he “bombarded [Greeves] with all the thin artillery of a seventeen year old rationalist”—but to little effect. For Lewis, there was simply no good reason to believe in God. No intelligent person would want to believe in “a bogey who is prepared to torture me for ever and ever.” The rational case for religion was, in Lewis’s view, totally bankrupt.

Yet Lewis found his imagination and reason pulling him in totally different directions. He continued to find himself experiencing deep feelings of desire, to which he had attached the name “Joy.” The most important of these took place early in March 1916, when he happened to pick up a copy of George MacDonald’s fantasy novel Phantastes. As he read, without realising it, Lewis was led across a frontier of the imagination. Everything was changed for him as a result of reading the book. He had discovered a “new quality,” a “bright shadow,” which seemed to him like a voice calling him from the ends of the earth. “That night my imagination was, in a certain sense, baptized.” A new dimension to his life began to emerge. “I had not the faintest notion what I had let myself in for by buying Phantastes.” It would be some time before Lewis made a connection between MacDonald’s Christianity and his works of imagination. Yet a seed had been planted, and it was only a matter of time before it began to germinate.

The Threat of Conscription

A somewhat darker shadow was falling on Lewis’s life, as it was on so many others. The ravages of the first year of war meant that the British army required more recruits—more than could be secured by voluntary enlistment. In May 1915, Lewis wrote to his father, outlining how he then saw his situation. He would just have to hope that the war would come to an end before he was eighteen, or that he would be able to volunteer before he was forcibly conscripted. As time passed, Lewis came to realise that he probably would be going to war. It was just a matter of time. The war showed no sign of an early victory, and Lewis’s eighteenth birthday was fast approaching.

On 27 January 1916, the Military Service Act came into force, ending voluntary enlistment. All men aged between eighteen and forty-one were deemed to have enlisted with effect from 2 March 1916, and would be called up as needed. However, the provisions of the Act did not apply to Ireland, and it included an important exemption: all men of this age who were “resident in Britain only for the purpose of their education” were exempt from its provisions. Yet Lewis was aware that this exemption might only be temporary. His correspondence suggests he came to the conclusion that his military service was inevitable.

Shortly after the March deadline, Lewis wrote to Greeves, borrowing Shakespeare’s imagery from the prologue to Henry V: “In November comes my 18th birthday, military age, and the ‘vasty fields’ of France, which I have no ambition to face.” In July, Lewis received a letter from Donald Hardman, who had shared a study with him at Malvern College. Hardman informed Lewis that he was to be conscripted at Christmas. What, he asked, was happening to Lewis? Lewis replied that he didn’t yet know. Yet in a letter to Kirkpatrick dated May 1916, Albert Lewis declared that Lewis had already made the decision to serve voluntarily—but wanted to try to get into Oxford first.

But events in Ireland opened up another possibility for Lewis. In April 1916, Ireland was convulsed with the news of the Easter Rising—an uprising in Dublin organised by the Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, aimed at ending British rule in Ireland and establishing an independent Irish Republic. The Easter Rising lasted from 24 to 30 April 1916. It was suppressed by the British army after seven days of fighting, and its leaders were court-martialled and executed. It was now clear that more troops would need to be sent to Ireland to maintain order. Might Lewis be sent to Ireland, rather than France, if he enlisted?

Meanwhile, Kirkpatrick had been pondering Lewis’s future. Taking his role as Lewis’s mentor very seriously, Kirkpatrick reflected on what he had discovered about his charge’s character and ability. He wrote to Albert Lewis expressing his view that Lewis had been born with a “literary temperament,” and showed a remarkable maturity in his literary judgements. He was clearly destined for a significant career. However, lacking any serious competency in science or mathematics, he might have difficulty in getting into Sandhurst. Kirkpatrick’s personal opinion was that Lewis should take up a legal career. Yet Lewis had no interest in following his father’s footsteps. He had set his sights on Oxford. He would try for a place at New College, Oxford University, to study classics.

Lewis’s Application to Oxford University

It is not clear why Lewis chose Oxford University in general, or New College in particular. Neither Kirkpatrick nor any of Lewis’s family had connections with either the university or the college. Lewis’s concerns about conscription had eased by this stage, and no longer preoccupied him as they once had. At Kirkpatrick’s suggestion, Lewis had consulted a solicitor about the complexities of the Military Service Act. The solicitor had advised him to write to the chief recruiting officer for the local area, based in Guildford. On 1 December, he wrote to his father to tell him that he was formally exempt from the Act, provided he register immediately. Lewis wasted no time in complying with this requirement.