I love my family, but I dote on my grandchildren. The sun rises and sets in their smiles and hugs. There’s nothing better than spending time with them—reading together, singing songs, praying, cuddling, planting flowers, dancing in rain puddles, assembling puzzles with them, baking cookies, cheering as they attempt new things like bigger slides and swings or sounding out hard words. I’m a typical grandma.

But grandmas weren’t always like that and children weren’t always cheered on. Once upon a time, in the days of my childhood and generations before, popular culture dictated that children were “meant to be seen but not heard.” Even my mother says that children in her day were meant to adapt to their grown-ups’ world and pretty much fend for themselves.

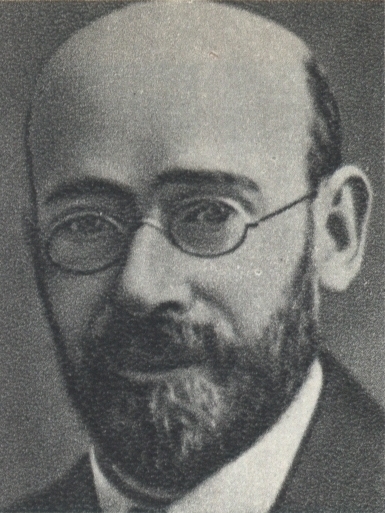

But not everyone believed that. Dr. Janusz Korczak (the pen name of Henryk Goldszmit), affectionately known as “Mister Doctor,” was a noted Polish pediatrician, author, and popular pre–WWII radio personality who bucked the system of his day. Even in the early 1900s, he advocated strongly for children and education reform. Dr. Korczak taught that children need love and understanding—ideas common enough now but radical then.

Dr. Korczak maintained that children are not meant to be shaped into adults by adults intent on fashioning children after themselves. He believed that children are unique souls rich in their own ideas, who deserve to be listened to and respected. Korczak wrote, “The unknown person inside each child is the hope for the future.”

His popular children’s book, King Matthew the First—the Polish equivalent of England’s Peter Pan—explores the conflicting relationship between a child and the powerful grown-up who oppresses him when that grown-up does not seek to understand or respect the child.

He cared about parents, too, aware that parents need to take time to understand themselves. He wrote, “Know yourself before you attempt to get to know children. Become aware of what you yourself are capable of before you attempt to outline the rights and responsibilities of children. First and foremost you must realize that you, too, are a child, whom you must first get to know, bring up, and educate.”

But he did more than talk—and write. After his service in WWI, he lived in and directed two orphanages in which he was able to implement his philosophies to good effect. Widely respected and read, Dr. Korczak lectured on radio and in universities and seminaries.

When political power in Poland changed to strongly support anti-Semitic agendas in the 1930s, Dr. Korczak’s life, along with that of every Jewish man, woman, and child, drastically changed. He lost many of the positions and opportunities he’d formerly enjoyed. He considered leaving Poland to pursue work in education in Israel, but before those logistics could be finalized, Germany invaded Poland.

Dr. Korczak protested the ill treatment of Jewish people under German occupation, but he continued his work with orphans, supplying them as best he could with food and other necessities. When Jewish people were forced to live in a walled ghetto in Warsaw, Dr. Korczak went to live in the ghetto with the children. He and other workers maintained the most normal and loving conditions that they could under the circumstances.

Though repeatedly offered sanctuary outside the ghetto by Polish friends and colleagues, Dr. Korczak refused to leave his children.

One of the most heartbreaking books I’ve ever read was Dr. Korczak’s Ghetto Diary, kept during his months directing the ghetto orphanage. It ends a few days before the dreaded SS call came outside the orphanage: “All Jews out!”

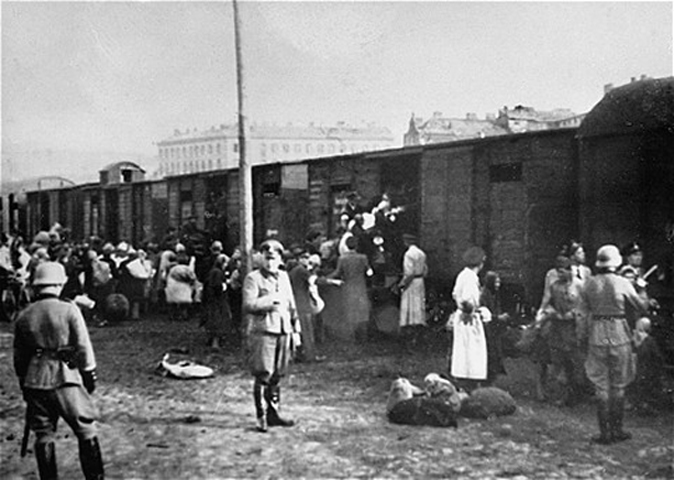

That morning, Dr. Korczak and the ten staff members working with him marched with 192 orphaned children, four abreast, through the broiling July heat to the Umschlagplatz, where German guards loaded the children and staff onto trains and sent them to Treblinka to be gassed.

Dr. Korczak, a hero, a man of conviction who lived as he spoke, shone as a bright light during Poland’s darkest days. History deservedly gives him the highest praise. He was a man who did what he could and one who laid down his life for his friends.

Thank you, Dr. Korczak, for showing us a better way.