This post was originally posted on Carla Laureano’s site.

I’m thrilled to welcome fellow Tyndale author Melanie Dobson to the blog today, especially since she’s talking about one of my favorite parts of writing–research! I’ve often said that writing was much different back when I was limited to what I could check out from the library or who I could reach by phone, so I love Melanie’s take on her research and writing process below. Join me in giving Melanie a warm welcome!

Write What You Don’t Know by Melanie Dobson

When I first started writing fiction, I was often told to “write what I know,” but I quickly realized that I don’t know that much, at least not enough to sustain a career as a novelist. After the release of my first novel, I wanted to learn much more, so I developed a research process that works for me, using the five resources below to build my contemporary and historical story worlds:

Surf the Web

The ideas for my novels come from many different sources, but I always partner with Google in the beginning to explore dozens of possibilities. When I wrote Chateau of Secrets, for example, I wondered if there were any Jewish men in Hitler’s army. I discovered online that there may have been 100,000 Jewish men who served in the Wehrmacht, and this startling fact became central to my plot.

In the past twenty years, I’ve read countless interviews, watched dozens of how-to videos, tested my main characters on sites like 16personalities.com, and connected with experts on a variety of topics. I’ve explored potential settings around the world through Google Earth VR and used social media to research the contemporary portions of my time-slip stories.

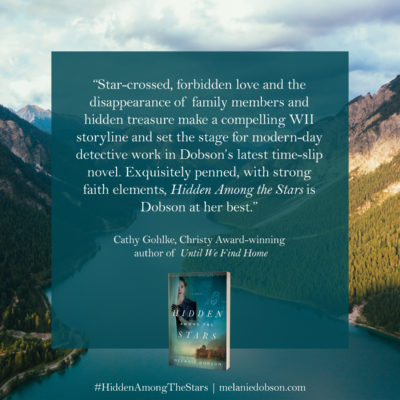

For my latest novel, Hidden Among the Stars, I searched online until I found the history of the Austrian lake castle that inspired my story and then contacted a violin maker in Salzburg who helped me create a character passionate about her violin.

For my latest novel, Hidden Among the Stars, I searched online until I found the history of the Austrian lake castle that inspired my story and then contacted a violin maker in Salzburg who helped me create a character passionate about her violin.

The Internet is fantastic for connecting people and to verify a number of facts (on reputable sites, of course), but online research is just the beginning. To dig deeper, I have to go offline.

Explore Museums and Living History

When I’m writing historical fiction, I’ve discovered that museums along with living history farms, exhibits, and towns like Williamsburg or Roscoe Village are gold mines. Each place offers an educational window to the past, and at these towns and exhibits, I’ve learned how to run a printing press, escape through a mine, load a rifle, break into an ancient coffin, pan for gold, and drive an Amish buggy. Things that would have been difficult to learn through written references or a video.

The tour guides at living history landmarks and museums seem to have accumulated more information than a textbook. The hands-on experience and the opportunity to email guides later with more questions is invaluable.

Invade the Library

Top secret—that’s what was stamped across the folder in England’s National Archives. To research Catching the Wind, I spent a day scouring recently released spy files outside London to learn about British citizens who had spied for Nazi Germany. The information I found in these files shaped my entire book.

Clothing catalogs, research papers, personal letters, magazines, and diaries—reference materials like these can be found in archives or a library. For historical research, these references provide basic information about attire and food during a specific era as well as more abstract concepts like how people approached life and what world events shaped their thinking.

For each new novel, I work closely with my local reference librarian to find the exact resources I need, and she helps me find answers to any lingering questions—like how British spies developed and hid microphotographs during the war.

Interview Experts and Locals

Interview Experts and Locals

Many people love to talk about their childhoods or hobbies or area of expertise, and if I tell them I write fiction, they’ll often give me much more information than I need for the book. Or at least, more than I think I’ll need…

Several months ago, I had the privilege of meeting with a Dutch Jewish gentleman who had been hidden away as a child during World War II. I befriended his sister online after reading a local news article, and she and her brother graciously opened up their world to me over coffee, sharing many personal stories about their own journey and their mother’s struggles and determination living in a concentration camp. Encounters like this one provide me with an enormous amount of information to build my story.

Because I write both historical and contemporary fiction, I’ve interviewed detectives, artists, Quaker friends, World War II heroes, and families of men and women who were part of the French resistance. I’ve spent hours listening to personal accounts about the inner workings of the Mafia, what it was like to grow up in a religious cult, and living in an England manor in the 1950s. Each person, each memory, redirects my plot and adds another layer of authenticity to a fictional story.

Visit the Location

When I researched Love Finds You in Liberty, Indiana, I spent several days climbing secret staircases and exploring other hidden places in homes that had once been stations along the Underground Railroad. I drove through the surrounding forest at night, and when I stepped out into the darkness, the owls hooted and the cloud cover masked the stars. My heart raced, and I felt terribly alone—a glimpse of what a runaway slave might have felt like in that horrible blackness, pursued by a slave hunter and his dogs.

When writers evoke the senses on paper, describing what the characters smell, hear, or taste, we invite readers to step directly into our story world. It can be challenging for me to describe the sensory information from a distant location, so I always visit my main settings, meeting the people and learning their stories even as I explore old towns and castles and gardens, scribbling down all the sights, smells, sounds, and tastes along the way.

With each of my novels, more than twenty of them now, I spend about a month slowly compiling the pieces needed to engage readers, typing all the information into folders on Scrivener. Because research has become my favorite part of writing, I have to deliberately set aside my mounds of background work after a month to begin putting my own words on paper. With the details now rooted in my mind, I’ll become completely lost in a story, and for the next three or four months, I’m writing about all that I’ve learned.