Finding Forgiveness When it Seems Impossible

On a frigid morning in November 1996, a little more than two years after Thomas was born, I woke up in a Washington, DC, hotel room, eager for the day to begin. I had been asked to speak at the annual Veterans Day ceremony held in front of the Vietnam Memorial on the famed National Mall. The invitation had come courtesy of Ms. Saywell, and while all of my attention was focused on this potential reunion with my ma and dad, it seemed a more immediate priority loomed for me—practicing that which I preached.

More than three thousand people were expected to attend, with additional tens of thousands watching on TV. I believed passionately in the remarks I had prepared and hoped that in some small way I could persuade those listening that regardless of the question, war never is the answer. I had discovered peace and wanted to share it. I had discovered love and knew of its healing balm. What I could not have anticipated was that my lofty theories about these moral ideals was about to be put to the grandest of tests.

Even though I laud the many benefits of knowing my Jesus, of surrendering to him and submitting to him, of obeying him and seeking to please him, I acknowledge that living for him comes at quite a high cost. For me, the weightiest aspect of remaining in relationship with Jesus was a little thing called forgiveness. I was grateful that God had forgiven me. But extending it to those who had wronged me, I was unsure if I could forgive.

The topic of forgiveness had initially surfaced for me years prior, long before I met Toan, when I had read two short verses of Scripture in the Gospel of Luke. Jesus said to his disciples: “But I say unto you which hear, ‘Love your enemies, do good to them which hate you, Bless them that curse you, and pray for them which despitefully use you.’”

This cannot be right, I thought. Maybe I misread it. I read the verses again, focusing on the last part this time around: “Bless them that curse you, and pray for them which despitefully use you.”

Bless them that curse me? Pray for them which despitefully use me? But how could this possibly be done?

I stared at those sentences for a long time and then began to laugh. “Oh, Lord!” I said aloud, “do you not recall how many enemies I have?”

So I began logging my “enemies list.” At the top of the list, of course, were all those involved in the destruction of my country and the dropping of the napalm bombs that forever changed my life. The strategists who drew up war plans, the commanders who ordered air strikes, the pilots who dropped bombs—I was furious with them all. I did not have names for all of these guilty parties, but I reserved places on my list for each one.

Next on my list were communist officials, man after man who had killed my dreams. They had used me for propaganda and had abused me day by day, and by way of recompense, I believed they should pay. If a person hits you one time or twice, perhaps forgiveness may be extended to him. But to suffer blow after blow, day after day, abuse after devastating abuse? That person must not be forgiven. I was surer than sure about that.

I sat with my list for the better part of an hour, adding names or positions as they came to mind, and at the end of the consuming exercise, I shut my Bible with more than a little force, thinking, Forgive them? Forget it. There is just no way. Christianity is too difficult a thing.

I struggled with the prospect of accepting and implementing those lofty sounding instructions. The wrongs that had been done to me were deeply grievous, and I feared that forgiving the wrongdoers would equate to dismissing or even approving of their sins. How would justice ever be served, I wondered, if I myself did not carry my cause?

And yet, I kept finding other Scriptures about forgiveness. I was being asked to be kind and tenderhearted, that vengeance was God’s responsibility, not mine.

I understood what God was asking, but I had many answers for God.

“Father, yes, but you do not understand how severe is my pain!”

“Yes, I know you say to forgive, but the terror, the destruction, the abuse, the scars!”

“Yes, I know that vengeance is to be yours, but all these years that have been taken from me! Is there not justice for me to be paid?”

“Yes, forgiveness is the wise thing to do, but Lord, I cannot ever forgive.”

“Yes, but . . .”

“Yes.”

“But . . . no.”

Even the honest question that Jesus’ disciple Peter posed regarding just how many times a godly person is to forgive fueled my fury. “Seven times?” Peter asked to which Jesus replied, “Seventy times seven.” That equals four hundred ninety times. For me, if I factored in well over a decade of tragedy and abuse from those on my list, the total came to four or five thousand wrongdoings against me. Why bother with only 10 percent of what was needed for me?

The lunacy of my thinking would not dawn on me until I stood at that point in time and space when I had to decide whether I would travel the road paved with life and peace and joy, or the one marked by suffering and bitterness and rage. Would I hand over my life to the lordship of Jesus or not? Which path would I choose?

I was shivering when I took the stage at last. “Dear friends,” I began with a quivering voice, “I am very happy to be with you today. . . . As you know, I am the little girl who was running to escape from the napalm fire. I do not want to talk about the war because I cannot change history. I only want you to remember the tragedy of war in order to do things to stop fighting and killing around the world. I have suffered a lot from both physical and emotional pain.

Sometimes I thought I could not live, but God saved me and gave me faith and hope. Even if I could talk face to face with the pilot who dropped the bombs, I would tell him we cannot change history, but we should try to do good things for the present and for the future to promote peace.”

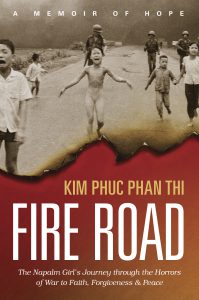

Adapted from Fire Road: The Napalm Girl’s Journey through the Horrors of War to Faith, Forgiveness, and Peace by Kim Phuc Phan Thi.