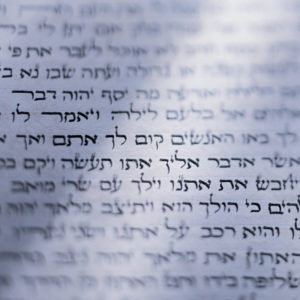

The Bible wasn’t written in any modern day language, but it was written in every day languages of the times. For many of us ancient Greek and Hebrew can seem sacred or special, but for the people in biblical times it was what they spoke every day. Since most of us don’t speak either of those languages we rely on translations to help us read God’s Word in our own every day language. But it can be exciting to dig into the original language and gain a personal understanding of the words of the Bible. Our Slimline Center Column Reference Bibles offer you just that opportunity. They include over 200 Hebrew and Greek word studies throughout the Bible text. These word studies give readers a glimpse into the inner workings of the New Living Translation and open a small window to the original languages of the Bible.

How to Do Word Studies with the Slimline Center Column Reference Bible

While reading through the Bible text, you will find at various places a superscript letter attached to the front of an English word. In the cross-reference column, there is a transliteration of the Hebrew or Greek word or phrase that underlies the translation at that point, along with the Strong’s number(s) in parentheses and the location of the next reference in that Hebrew or Greek word chain. If you follow the reference chain, eventually you will read through all of the marked instances of that word or group of words in the entire study Bible. Doing so is a good way to begin doing Hebrew and Greek word studies.

Another way to use the tool is to systematically study a particular word from those listed in an NLT Slimline Center Column Reference Bible. In these Bibles we have listed and defined all of the words that are included in the Hebrew and Greek word-study chains. The references in the chains are selective and do not represent all of the places where a Hebrew or Greek word occurs in the Bible; we chose a limited number of instances in order to show the variety of usage for a given term or group of terms. If you want to do a complete study of a biblical word, it would be a good idea to read most or all instances, which you can find with Strong’s Concordance or a similar tool.

You can take your study of Hebrew and Greek words further by obtaining a copy of Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Dr. James Strong first published his exhaustive concordance of the King James Version in 1890, and the system he created for referring to every individual word in Hebrew and Greek by a number has been tremendously helpful for English readers who want to do word studies in the original languages. The Strong’s numbering system has become the de facto standard for English language word-study tools. There is a wide variety of other publications and software tools available with which you can take your study of any Hebrew or Greek term further.

The dictionary and index in an NLT Slimline Center Column Reference Bible is organized using the Strong’s numbering system, named for the system used in Strong’s Concordance. For any word you find while reading the text, you will simply have to use the Strong’s number to find the brief definition and full chain. Please note that there are separate numbers and lists for the Hebrew words in the OT and the Greek words in the NT.

If you follow the entire word chain, note each context in which the word occurs and how it has been translated. You will get a good feel for the range of uses that each word can have, and you will get a unique glimpse into the inner workings of the NLT.

Hebrew and Greek Word Studies

Because the Bible was originally written in ancient languages that are quite different from our own, the Hebrew and Greek words of the original text are often seen as strange and wonderful. Sometimes, Greek and Hebrew words are portrayed as though they are somehow a special or “divine” language containing more significant meaning than normal languages like English. In truth, biblical Greek and Hebrew are normal human languages, with words that are similar to the words of any language.

Words are complex animals. Consider, for example, the word animal in the previous sentence. In most contexts, that word conjures up images of wildlife. In this particular instance, however, it means something quite different. Words have a dynamic relationship to meaning, neither confined to a dictionary entry nor free to mean anything at all. Few readers whose mother tongue is English would have misunderstood the meaning of the sentence, “Words are complex animals,” but it could certainly cause confusion for a reader whose knowledge of English is minimal.

When confronted with a word from any foreign language, especially an ancient one like the Hebrew or Greek of the Bible, people can misunderstand if they aren’t careful to study the word in a way that makes sense with how language is used. Some common mistakes that are made in studying words in the biblical languages include the following:

- Assuming a word means more than it does. When faced with the range of meanings a given word can have, sometimes interpreters are tempted to think that every instance of that word contains all of the possible meanings. While it is true that sometimes a writer will purposefully use a word to mean more than one thing, it is not common. Normally, a word has one meaning in a given context. For instance, the Hebrew zera‘ (2233) can mean “seed” or “offspring,” but only rarely would both meanings apply to one specific use of the word. An important part of original-language Bible study is to discern which meaning a term probably has in a given context.

- Understanding words by their roots. Many words share common roots, but this does not necessarily mean their meanings are related. The meaning of a word is related to how it is used in the language, not where it came from. The Greek ekkle¯sia (1577) comes from two words that mean “to call” (kale¯o) and “out of” (ek). This does not mean that ekkle¯sia means “called out of,” any more than the English word goodbye means “it’s good that you’re leaving.” It is important to understand the meaning of the word from its usage rather than its roots.

- Confusing synonyms. Many words share common meanings, or at least have very similar meanings in specific contexts. An example in English is “choose” and “select.” In many cases, the difference is negligible, and a writer could choose between them without changing the meaning at all. But in some contexts the selection is meaningful. In this tool, we sometimes string synonyms together in a single chain, but that does not mean they are completely interchangeable. Each word must be considered on its own terms in each context.

- Failing to appreciate the difference between words and concepts. Words are only tools to communicate meaning, so any one word will never be sufficient to get a complete picture of an important concept. If you want to understand the concept of “truth” in the Bible, Hebrew ’emeth (0571) is a good place to start, but to limit study to a word alone will miss important components of the biblical picture of truth. Each concept must be studied as whole, going beyond the study of words.