“Going to various counselors has been a positive experience for me, but there’s no question that one of the most powerful aspects of these interactions was that someone wanted to hear my story. ‘Tell me more’ was a welcome invitation.”

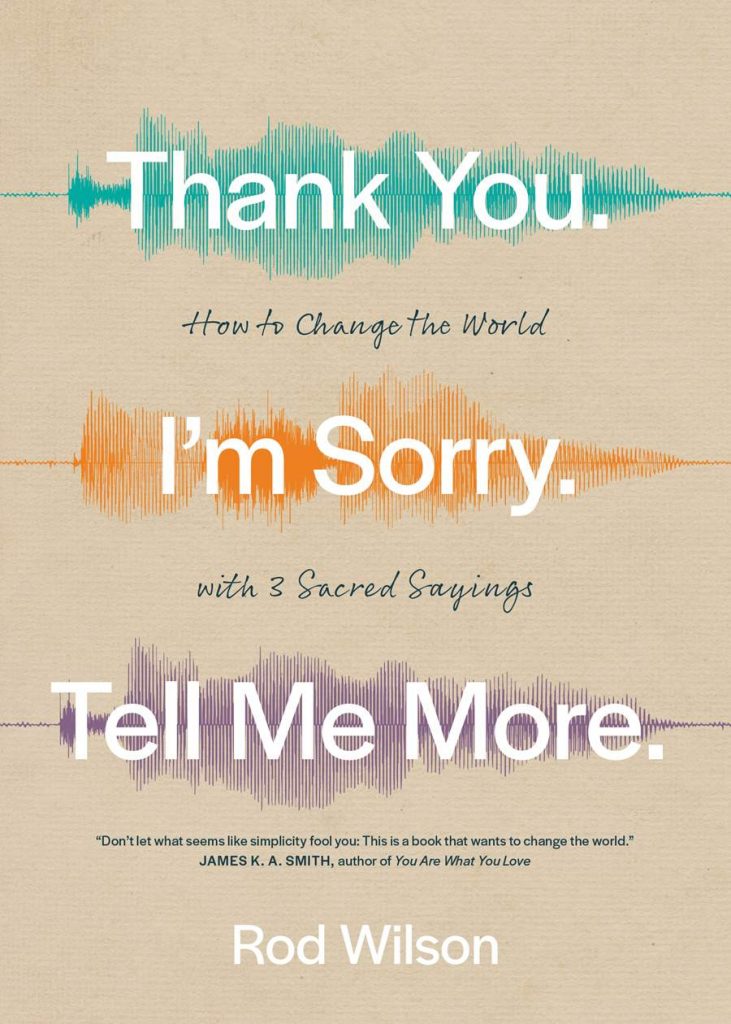

By Rod Wilson, excerpted from the book Thank You. I’m Sorry. Tell Me More.

Much of Western culture is in the grips of entitlement, victimization, and individualism, with the consequence that it’s challenging and countercultural to say “Thank you,” “I’m sorry,” or “Tell me more.”

Entitlement. Newborns are captivating. Cute and adorable, they’re the center of attention at Christmas, political rallies, and local malls. Their daily lives are interesting. Food, the sole responsibility of the parents, comes in one end regularly, often on demand. (To translate, “on demand” means screaming, yelling, crying, or some combination of all three.) After due process, the waste comes out the other end, and it’s the parents’ responsibility to deal with the consequences of that action, one that employs almost all five senses. That process is sometimes on demand as well. A dirty diaper, after all, isn’t pleasant for the tiny infant, so he may well scream, yell, or cry. Apart from the odd smile, a lot of sleeping, and a few other “look at what he did” gestures, this is early life for the new baby. He makes demands for special treatment, and his parents oblige.

You can imagine the shock if the two-month-old sat up in his crib and exclaimed, “Thanks so much, Mom. That was an outstanding change. I feel much better now. Feel my gratitude.” For developmental reasons, both physical and verbal, we know that wouldn’t happen, but we also know it wouldn’t occur because infants deserve special treatment. They have a right to be treated that way. Special privileges are appropriate when you are two months old. We don’t expect them to say “Thank you,” although many parents would value just a little bit of appreciation in those early years.

One of the major problems with many post-infant people? Life doesn’t change all that much. While I may not cry and yell with infant-like expressions, I do the same in more sophisticated and subtle “adult” ways. Sadly, this tendency is frequently reinforced by parents who, having lived the infant years responding on demand to “feed me” or “change me,” have continued to cater to the demands and expectations of their older children in such a way that entitlement runs deep.

Outside the home, entitled adults then get exposed to the marketing of a consumerist culture. We learn that we deserve easy credit, loans, homes, holidays, and credit cards. We experience deep disappointment when our perception of what we deserve in our workplace and marriage, what we expect from our mosque, church, or synagogue, and what we want from our politicians don’t come to fruition.

At the core of entitlement is a problem with saying “Thank you” because of a high commitment to thinking I deserve it. If something is deserved, why would you say “Thank you”?

Victimization. A pivotal moment in debates around the social, legal, moral, and psychological issues related to being sorry and victimization occurred in a 1992 legal case. Stella Liebeck ordered a coffee from a drive-through window at her local McDonald’s in Albuquerque, New Mexico. As she pulled the lid off to add cream and sugar, the whole cup of coffee spilled on her lap, burning her to such a degree that she required skin grafting and lengthy rehabilitation. Lawyers took the case on, suing McDonald’s for negligence because the coffee was dangerously hot—and at a much higher temperature than how other establishments served coffee. Jury deliberations led to McDonald’s being held 80 percent responsible for the burns and Liebeck being held 20 percent responsible.

Some accused Liebeck’s lawyers of initiating a frivolous suit, but we can now look back with the perspective of thirty years and realize that this case predicted much of contemporary culture. Even though Stella spilled her coffee because she put it between her knees and took off the lid, a lawsuit with a minute analysis of the temperature of the coffee was appropriate. She wasn’t entirely to blame for what happened but was a victim of a fast-food chain. The lawsuit made a poignant point about the allocation of wrong.

It’s straightforward to move into the space of the victim. The social sciences have helped us frame the present in light of the past, and we’re in a cultural moment where what’s “wrong” is up for discussion. I’m not responsible because of this or that, this line of thinking goes, so why would I say “I’m sorry”?

“I know you struggle to deal with my anger,” says the father to his daughter, “but you need to understand that it comes up because of my historical sense of being marginalized.” “I know I hurt you by having multiple affairs,” says the husband to his wife, “but I made a mistake, and a lot of it is due to my underlying need for affection.” The mathematical equation is explicit—

marginalization = anger + abuse of others.

Or

need for affection = multiple affairs + hurting

spouse.

If that’s where the angry father and the unfaithful spouse stay, they’ll display classic victimization. They bear little responsibility for their influence on others and have no sense they need to say “I’m sorry.” Someone, or something, else is to blame.

While “Thank you” acknowledges others have impacted us, “I’m sorry” reflects an awareness that we have impacted others. It’s the opposite of “It’s not my fault.” Blame shifting and converting reasons into excuses gets us off the hook. We can spill our coffee, hit our sibling, be angry with our children, cheat on our spouse, and justify and legitimize what we did by holding people or circumstances responsible. In the process, we fail to acknowledge the experience of the other, and they never hear “I’m sorry.”

Individualism. I once taught an introductory counseling course in Africa. One day a student asked, “So you are telling us that in North America, when people have a problem, they meet an individual stranger, who may be younger than them, in an office and pay them money for advice?” If you’ve had much cross-cultural experience, you’ll understand the predicament. Part of you wants to say, “Yes, what’s the problem with that?” but then you dread that your Western bias isn’t shared everywhere, and you know that the teacher is about to become a student.

“What do you do here if you have a problem?” I asked.

She responded, “We go to the town center and meet with a group of elders in a circle. The youngest one speaks first and the oldest one speaks last as we go around the circle sharing opinions. We believe that community is key in our healing.”

That interaction and many others since have made me acutely aware of the difference between seeing people as part of a community versus seeing them as individuals. In the West, being true to ourselves has become a virtue, and we prize privacy, self-direction, and independence. And now we have an entire industry helping us do self-care, as the individualism project has left us with wounds and warts.

The title of Sherry Turkle’s book Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, captures our current predicament all too well. We have unprecedented access to information. Connecting with people instantly in any part of the world is straight forward. So-called friends are accessible to us through multiple technological devices. But we are alone. Our sense of community seems to be decreasing as our experience of isolation and loneliness increases.

Many of us are paying consultants, trainers, coaches, mentors, counselors, spiritual directors, and the like to help us improve, support us in accomplishing a goal, and provide input as we deal with challenges. I suspect an underlying dynamic driving these legitimate pursuits is finding places where someone will listen to our stories. Where someone will ask us to tell them more. Going to various counselors has been a positive experience for me, but there’s no question that one of the most powerful aspects of these interactions was that someone wanted to hear my story. “Tell me more” was a welcome invitation.

While “Thank you” acknowledges others have impacted us, and “I’m sorry” reflects an awareness that we have impacted others, “Tell me more” is an affirmation that we impact each other. But we have to deal with the cultural hurdles of entitlement, victimization, and individualism in using these phrases.

You’ve been reading from

Thank You. I’m Sorry. Tell Me More. by Rod Wilson

In this simple yet profound book, clinical psychologist Rod Wilson introduces us to the sacredness of these familiar but forgotten sayings. What impact do these sayings have on our relationships?

When we say, “Thank you,” we acknowledge the way others impact us.

When we say, “I’m sorry,” we acknowledge the way we impact others.

When we say, “Tell me more,” we acknowledge the way we impact each other.

Try it. Read this book and be encouraged and equipped to deliver kindness in your speech. As you engage with these three phrases more thoughtfully and speak them more frequently, you will enjoy a life full of deeper friendships and joy.

About the Author

Rod Wilson has worked as a psychologist, served as a pastor in three different churches, and held multiple roles in theological education, including President of Regent College in Vancouver, Canada from 2000-2015. Rod currently works with Lumara Grief and Bereavement Care Society, A Rocha, the Society of Christian Schools in BC, and In Trust Center for Theological Schools, and maintains an international teaching and mentoring ministry. His upcoming book, Thank You. I’m Sorry. Tell Me More., releases from NavPress in January 2022.