“Family stories also make great fodder for novelists.”

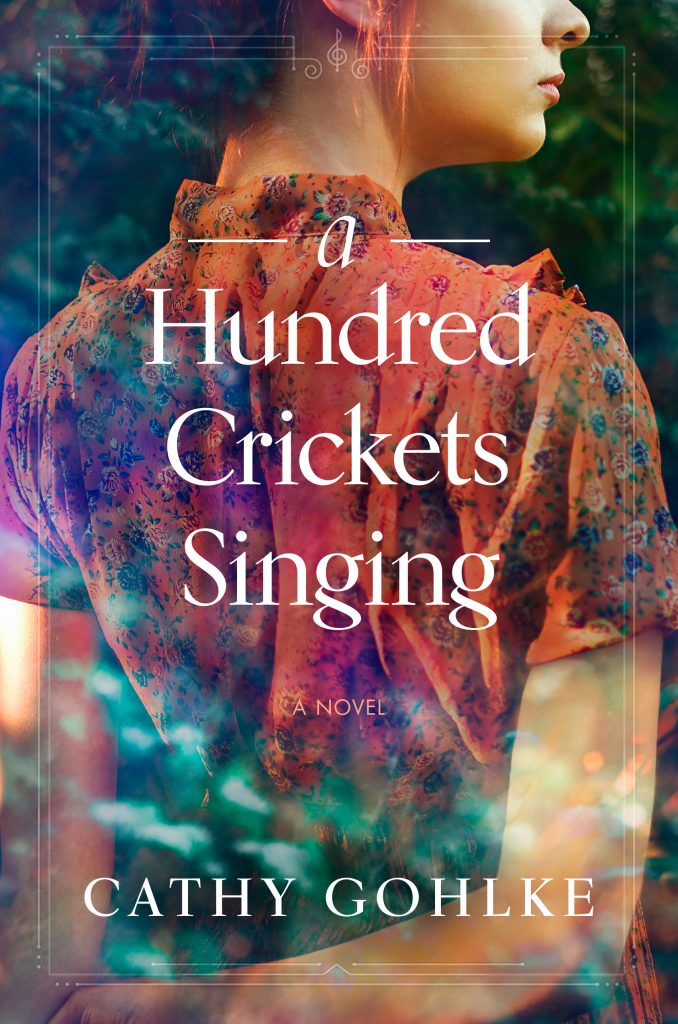

By Cathy Gohlke, author of the book A Hundred Crickets Singing

Family stories influence generations. Researchers say those who grow up hearing and learning to retell family stories develop a stronger personal identity and security. Children feel more confident knowing from whom and from whence they came. Family members—the lovable, adventurous, courageous, determined, faith filled—all help children identify the character of their family and give them a bar to aspire to, a bar to maintain.

Family stories also make great fodder for novelists. Every family has that endearing relative with quirky behaviors or astounding skills, or perhaps someone who has overcome great odds, achieved great things, or acted with immeasurable compassion, or even made the ultimate sacrifice.

But what if our family stories are not admirable? What if there are old bones that rattle in our closets in the dead of night of which we are ashamed, tales we’d rather the world not see, let alone read about in our fiction? Yet what if those true stories hold the best and most valuable life lessons? Can we still use them, if we don’t hurt others, abuse privacy issues or confidences, implicate or slander folks? It’s an important question for novelists.

I grew up with the lines of Beth Day’s poem about the three gates engraved in my mind and across my heart. The gist of that poem is that in considering telling any tale of another, we must make it pass through three gates of gold: Is it true? Is it needful? Is it kind?

Those three gates give me caution when infusing fiction with family stories, even the most intriguing tales, flattering or not. Usually, those tales pass the first gate—it’s true. Sometimes they pass the second gate—it’s needful—for the sake of a valuable lesson learned or so that a similar disaster may be avoided in the future. But that third gate, is it kind, can squelch some of the most riveting stories.

In the writing of Night Bird Calling and A Hundred Crickets Singing I drew on family stories, personal experience, and interviews as well as books, county histories, newspapers, archives, etc. No small amount of imagination threaded and rounded out those true stories.

One woman shared her story with the suggestion that I include it in my book—for it fit my research so well—but made me promise that I not tell her family members until after she passes, when “everybody involved will be dead.” I’ll keep that promise, but I recorded her true story because I know her family members will want to separate fact from fiction, and time plays havoc with memory. Ironically, once the book released, she decided she didn’t mind her family knowing. In fact, she was proud of the memory, as well she should be.

One story character was drawn from the Civil War archives of my great-great-grandfather—a poor man with little education, unlike the aristocratic character portrayed in A Hundred Crickets Singing. I don’t think my ancestor would mind my rattling of his bones. His story’s already been recorded in the archives in Washington. However, not everyone will see his actions as admirable, as I do. That’s one of the facts of fiction.

When drawing inspiration from the tales of real-life people I do not use their names, even in my notes to readers or interviews, unless their actions are part of historical record, admirably portrayed, or I’ve been given permission. If the inspiration for a character is in some way disreputable, abusive, or dishonorable, I might draw from the experience but do not name names, do not point fingers.

Fiction is not a punching bag for those who’ve failed, nor is it our opportunity for revenge. I grew up hearing “the church is a hospital for sinners, not a rest home for saints.” That truth grows clearer with every passing year.

Just as in life, not every character in our stories will see the error of their ways. Not everyone repents, overcomes, or grows into a relationship with our Lord. Some characters remain broken. That shows real life and demonstrates consequences for actions—valuable lessons in fiction and in life.

Stories, like real life, are most satisfying when mistakes, sins, and hard lessons lead to repentance, to a surrender to the One who loves us best and most, and to the person ultimately claiming victory in Christ Jesus. Writing stories that show characters recognizing their need and seeking the One who can fill it, then leaving their past behind and stepping into the future with Him, is what writers of Christian fiction work to do. From the character’s perspective, that’s the mercy of grace and the birth of hope.

I’m reminded of something Oswald Chambers wrote—a quote I need and love so dearly it is written on a plaque in my office where I see it daily: “Our yesterdays present irreparable things to us; it is true that we have lost opportunities which will never return, but God can transform this destructive anxiety into a constructive thoughtfulness for the future. Let the past sleep, but let it sleep on the bosom of Christ. Leave the Irreparable Past in His hands, and step out into the Irresistible Future with Him.”

In life, in fiction, our bones and the bones of those we love may rattle, but let them rattle for a purpose, for a reason. Let our Lord redeem us and them. It’s what He does best. It’s what we love most about life and about fiction.

Question: What stories do you hope your children and grandchildren will remember? Which ones do you hope they’ll take to heart in building their lives and characters, and then pass down to future generations?

You might be interested in

A Hundred Crickets Singing by Cathy Gohlke

In wars eighty years apart, two young women living on the same Appalachian estate determine to aid soldiers dear to them and fight for justice, no matter the cost.

1944. When a violent storm rips through the Belvidere attic in No Creek, North Carolina, exposing a hidden room and trunk long forgotten, secrets dating back to the Civil War are revealed. Celia Percy, whose family lives and works in the home, suspects the truth could transform the future for her friend Marshall, now fighting overseas, whose ancestors were once enslaved by the Belvidere family. When Marshall’s Army friend, Joe, returns to No Creek with shocking news for Marshall’s family, Celia determines to right a long-standing wrong, whether or not the town is ready for it.

1861. After her mother’s death, Minnie Belvidere works desperately to keep her household running and her family together as North Carolina secedes. Her beloved older brother clings to his Union loyalties, despite grave danger, while her hotheaded younger brother entangles himself and the family’s finances within the Confederacy. As the country and her own home are torn in two, Minnie risks her life and her future in a desperate fight to gain liberty and land for those her parents intended to free, before it’s too late.

With depictions of a small Southern town “reminiscent of writings by Lisa Wingate” (Booklist on Night Bird Calling), Cathy Gohlke delivers a gripping, emotive story about friendship and the enduring promise of justice.

About the Author

Four-time Christy and two-time Carol and INSPY Award–winning author Cathy Gohlke writes novels steeped with inspirational lessons from history. Her stories reveal how people break the chains that bind them and triumph over adversity through faith. When not traveling to historic sites for research, she and her husband, Dan, divide their time between northern Virginia and the Jersey Shore, enjoying time with their grown children and grandchildren.

Visit her website at cathygohlke.com and find her on Facebook at CathyGohlkeBooks.